The Rise of Nuclear Verdicts

“Nuclear verdicts” in employment cases are growing in frequency and severity. A couple of examples: a June 2022 verdict in California for $464 million in a case alleging sexual and racial harassment; an October 2022 Texas verdict for $366 million in a case alleging racial bias. While opinions about the causes of this “nuclear age” vary, employers must have a strategy for dealing with cases with very bad facts, including bad conduct, bad documents, and bad management employee witnesses. In this interactive session on hyper-sensitive topics, our panelists will provide practical and litigation advice for real life scenarios for employers facing potentially nuclear cases. This paper is intended to be an introduction to the presentation rather than a full exploration of the issues and solutions that will be discussed.

Some commentators have defined “nuclear verdicts” as a verdict of $10 million or greater. Those verdicts have become increasingly more common. The National Law Journal reported the average jury award among the top 100 U.S. verdicts more than tripled between 2015 and 2019, skyrocketing from $64 million to $214 million. Furthermore, 30% more verdicts surpassed the $100 million threshold in 2019 compared to 2015.[1]

We are entering the ThermoNuclear Age. The first question is why? The second question, and the focus of this presentation, is what can employer defendants do about it?

Suggested causes for higher verdicts in all cases include: (1) the perception of the value of money has changed; (2) media outlets and social media impact on public opinion; (3) the erosion of caps on punitive damages; (4) erosion of tort reform; (5) litigation funding; and (6) use of the reptile strategy at trial. But as applied to employment cases, these factors, along with the Covid, can have an even greater impact.

Juror Decision-Making in Employment Cases

In employment cases, survey after survey reveals the risks to employers of taking a case to trial. One national jury consultant concluded in a 2016 article that jurors in employment cases do not care about evidence.[2]

Possibly more than in any other type of litigation, people feel uniquely qualified to sit as jurors on employment cases. “More than 50% of jurors’ time in deliberation is spent… talking about their jobs and related experiences”.

In evaluating the strength of an employment case, one key factor to consider is the degree to which the specific issues are likely to support or challenge jurors’ perceptions of themselves and their environment.

Most people derive their self-concept from their jobs. Even for those people who don’t derive intrinsic satisfaction from their work, the job defines the way they spend a great deal of their waking hours, sustains them, and brings routine and stability to their lives.

At some level, most people fear losing their jobs. Many have a close friend or relative who has experienced a serious problem at work. Consequently, people who sit on juries find it rather easy to identify with the fear, anguish and humiliation plaintiffs report due to unfair treatment at work, no matter how exaggerated or baseless they appear to defense attorneys.

Effective trial attorneys recognize and exploit the link between self-concept and job-related issues. During voir dire, they spend more time listening than talking to jurors about their negative and positive experiences in the workplace, feelings about the stability and fairness of their current job situation, and fundamental attitudes and values toward employer-employee relations…

Effective opening statements, witness testimony and closing arguments also take advantage of the importance of self-concept in employment disputes…

Jurors hold employers to very high, sometimes unattainable standards when it comes to disciplining, demoting, firing, and protecting employees. Jurors expect clear, written policy on anything that affects employees. Jurors expect clear, fair, consistent performance evaluations. They expect clear and consistent written communication…

In short, in employment litigation, jurors expect just about everything that almost never happens. Before demoting or firing, jurors expect an employee to receive a series of warnings, counseling/coaching sessions, training sessions, job adjustments, more warnings, more coaching, and when, and only when, everything else has failed, at least one more warning.

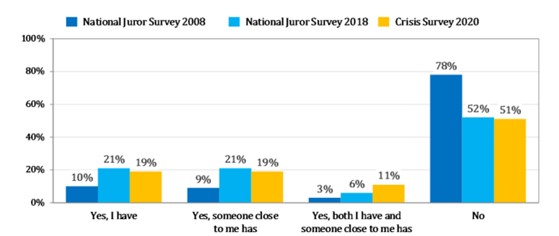

That same jury consultant company conducted a national jury survey in 2008, 2016, 2018, and 2020 on employment cases generally, and found that, combined with their case studies since 2000, several attitudes about discrimination and harassment in the workplace have remained relatively consistent.[3]

- 60% agree that racial discrimination is common in the workplace.

- 66% believe most discrimination lawsuits are justified.

- 75% believe most harassment lawsuits are justified.

- 70% believe that retaliation is common after an employee complains of harassment.

In that company’s 2008 National Juror Survey, 22% of the respondents reported that they, or someone close to them, had experienced sexual harassment in the workplace. Ten years later, in the 2018 National Juror Survey, more than double that percentage of respondents (48%) indicated that they, or someone close to them, have experienced sexual harassment in the workplace. This increase could be a result of the “me too” movement, but could be attributable to other trends.

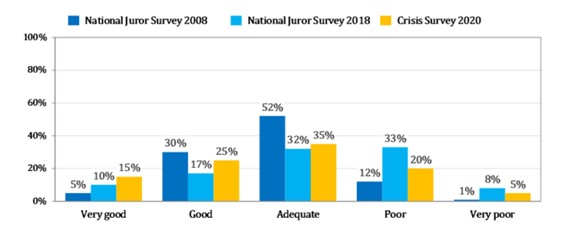

Another notable survey finding was that the impression that corporate America is or isn’t doing a good job in fighting sexual harassment in the workplace.

How good of a job has corporate America done in fighting sexual harassment in the workplace?

Current Research on the Impact of Covid on Juror Decision-Making

There is no question that the Covid epidemic has had an impact on juror decision-making. Note the findings in the excellent article by Dr. Lorie Sifacuse of ALFA International Gold Sponsor Courtroom Sciences, Inc. entitled “Impacts of the COVID-19 Crisis on Jurors’ Attitudes and Decisions”.[4] Dr. Sifacuse states that a 2020 survey indicated that 71% of a nationally representative adult sample were concerned about the Coronavirus’ implications for their personal health. Nearly half (49%) said that the stress and anxiety caused by COVID-19 has been challenging for them. About 40% said that the COVID-19 crisis has caused financial stress, and 28% said that it has negatively impacted their relationships. Increased stress and uncertainty, fear of illness and death, and other changes in psychological health and well-being can dramatically affect how individuals process information and make decisions.

Dr. Sifacuse posits that there are four primary changes to expect in civil jurors’ attitudes and decision-making as a result of the COVID-19 crisis:

Polarization

What does the research say about individuals who are stressed, uncertain, and fearful? One key finding is that these individuals will adhere to and defend their pre-existing attitudes and beliefs, and often become more polarized.

Jurors who were previously anti-corporate will likely at the very least retain that position, and many will likely become more anti-corporate.

Ingroup Favoritism and Outgroup Bias

Psychological theory and research predicts that many jurors may be increasingly judgmental of individuals who do not share their ethnicity, background, or beliefs; jurors also may have more positive perceptions of individuals who appear similar to them.

Increased Reliance on Intuition, Emotion and Heuristics

Psychological research identifies two main information processing modes, or ways in which individuals attend to and process information to make decisions: logical processing mode and intuitive mode.

Ultimately, both psychological research and common-sense point to an increased likelihood that jurors will follow the intuitive processing mode in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis. This, of course, can make jurors more susceptible to typical pro-plaintiff narratives. Jurors also may increasingly rely on heuristics, cognitive shortcuts, or “rules of thumb for reasoning” in their decision-making.

Even though jurors will have to wait to hear the defense case, counsel can tailor their approaches and tactics to appeal to intuitive information processors. Thorough and systematic refutations of the plaintiff’s allegations will not be effective in persuading jurors during and after the COVID-19 crisis. Instead, the defense must advance a simple, linear, and relatable pro-defense narrative that preferably highlights the conduct of the key parties and no more than 2-3 key defense themes.

Increased Focus on Rules and Rule-Breaking

Evidence indicates that rules and conventions have become more important among individuals who fear contagion.

Those who fear contagion place an increased importance on ingroup loyalty. They also tend to show a greater deference to authority figures and a decreased tolerance for those who defy authority.

Counsel should anticipate some basic overall changes in jurors’ perceptions and decision-making resulting from increased adherence to rules and minimized tolerance for rule breaking. The most obvious change is an increased susceptibility to plaintiff reptile tactics.

In order to defeat a well-executed plaintiff reptile approach, the defense must swiftly and assertively advance a counter-narrative identifying the responsible party or parties.

Juror Attitudes in the Age of Covid

During the pandemic, DecisionQuest’s national jury survey included a brief case summary of a discrimination and harassment lawsuit scenario and asked respondents to render decisions on liability and damages.[5]

The case scenario presented to respondents involved a female plaintiff with claims of harassing behavior of a sexual nature, retaliation, and lack of action by management. The allegations described inappropriate comments and actions by a manager that gradually escalated in severity, culminating in a negative rating by the manager following the plaintiff’s rejection of the manager’s request to begin a sexual affair. She alleged that this resulted in the loss of a raise received by comparable employees and that when she brought a complaint to HR, management retaliated by putting her on probation and firing her a month later.

Her case was contrasted with defense arguments of a poor performing employee (with documented warnings in her file), and falsifications on her employment application. Witnesses testified that the plaintiff’s attitude and performance changed after a different coworker had broken off an affair she had been having (in violation of company policy). The company also argued that appropriate affirmative actions were taken against the alleged harasser, including forcing him to take early retirement. Since she did not report the harassment for several months, the company says it is not liable for the inappropriate behavior of her manager, so her employer should not have to pay any damages and should not be punished. Respondents were asked which party they favored, what amount of claimed damages ($10 million) they would award and the extent to which the corporate defendant should be punished.

- The majority (73%) of respondents favored the plaintiff and the remaining 27% favored the defense.

- In terms of damages:

- 17% said they would award nothing.

- 32% said they would give one fourth of what was requested.

- 25% said they would give half of what was requested.

- 15% said they would give three fourths of what the plaintiff requested.

- 5% said they would award all of the damages claimed.

- 6% of respondents said they would give everything the plaintiff asked for plus more.

- More respondents than not said that the employer deserved to be punished in the case:

- 10% said “not at all”.

- 23% said “a little”.

- 38% said “some”.

- 29% said that the employer “very much” deserved to be punished.

DecisionQuest noted that several factors were reliably associated with verdict decisions:

- Respondents endorsing beliefs that women are often denied opportunities for advancement because of their gender were statistically more likely to find in favor of the plaintiff and to award her higher damages.

- Respondents holding a strong opinion that women who raise harassment complaints are retaliated against were statistically more likely to find in favor of the plaintiff and to award her higher damages.

- Respondents with greater anger against corporate America were statistically more likely to find in favor of the plaintiff and to award her higher damages.

- Respondents who believe sexual harassment lawsuits are usually justified were statistically more likely to find in favor of the plaintiff and to award her higher damages.

- Respondents who indicated higher levels of concern that they or someone they know will become infected with the novel Coronavirus were statistically more likely to find in favor of the plaintiff and to award higher damages.

What Companies Can Do to Minimize the Risk of Bad Cases Going Nuclear

In the presentation, we will focus on the strategies and practices employed by employers to deal with cases with “bad facts” at multiple stages: (1) the Investigation/ Initial Complaint phase; (2) the Pre-Litigation/ Claimant is Represented phase; and (3) the multiple subphases in the Litigation Phase, including: (a) discovery; (b) mediation; (c) Pre-Trial and (d) Trial.

How to Defuse the Bomb: Be Proactive

Our panelists will discuss their companies’ strategies when they see “bad facts” and recognize that an employee is responsible or that HR did not handle the process appropriately. But they have to prevent bad cases from occurring in the first place. They have various mitigation strategies that keep cases from going nuclear, including the following practices:

- Implement vigilant hiring processes for all positions.

- Utilize periodic, documented reviews to better gauge employees’ work performance over time and take any complaints filed against staff seriously.

- Ensure compliance. Regularly assess workplace policies to maintain compliance with negligent hiring, retention, and supervision laws as well as any other applicable federal, state and local regulations. Consult legal counsel for additional compliance assistance.

- Create a culture of responsibility and accountability.

- Utilize a robust investigation process; HR does not recommend resolutions.

- Get detailed affidavits from employees before they become uncooperative or don’t work for the company anymore.

- Elevate any problematic cases to legal immediately.

- Utilize a specially assigned in-house ADR person who is experienced and skilled at finding resolutions.

- Mediate every EEOC complaint, and find quick and small solutions if possible.

- Utilize “culture coaches” that investigate bad claims, with an internal docket for responding to claims; keep the complainant in the loop; you want the complainant to feel heard.

- Require mandatory arbitration of all employment cases. That mandatory arbitration provision has always been upheld when challenged.

- If a manager has done a “bad thing,” suspend them with pay during the investigation; try to wrap it up within 10 days.

- Demand letter phase:

- Handle as much as you can in-house.

- Might have outside counsel do the investigation if necessary to preserve attorney client privilege; call the plaintiff’s counsel and ask for substantiation.

- Strongly encourage pre-suit mediations.

- In litigation, rely on outside counsel to manage “bad witnesses”, but have to make sure that discovery does not go financially nuclear.

- Settle “bad cases” before “bad facts” get disclosed in discovery;

- Terminate “bad actor” employees quietly.

- When dealing with potentially explosive cases, make sure that you have counsel that you trust, and has good trial experience; performance of counsel is just as important as performance of your witnesses.

- Conduct mock jury exercises when appropriate.

- Try to remember the goal is to remain out of trial.

- If going to trial, be prepared; be prepared; be prepared. Hire excellent counsel. Tell the company’s story. Humanize it.

- Defuse the jurors’ anger. Be reasonable.

- Show the jury the company cares. Accept responsibility if the situation calls for it.

[1] ttps://coverlink.com/case-study/nuclear-verdict-case-study-464-million-employment-practices-liability-loss/

[2] https://www.decisionquest.com/why-jurors-in-employment-cases-dont-care-about-evidence/

[3] These statistics and the following 3 charts can be found at https://www.decisionquest.com/juror-attitudes-in-the-age-of-the-coronavirus-discrimination-and-harassment-lawsuits/

[4] https://www.courtroomsciences.com/blog/litigation-consulting-1/impact-of-the-covid-19-crisis-on-jurors-attitudes-decisions-132; https://www.courtroomsciences.com/blog/litigation-consulting-1/impact-of-the-covid-19-crisis-on-jurors-attitudes-decisions-133; https://www.courtroomsciences.com/blog/litigation-consulting-1/impact-of-the-covid-19-crisis-on-jurors-attitudes-decisions-134; https://www.courtroomsciences.com/blog/litigation-consulting-1/impact-of-the-covid-19-crisis-on-jurors-attitudes-decisions-135

[5] https://www.decisionquest.com/juror-attitudes-in-the-age-of-the-coronavirus-discrimination-and-harassment-lawsuits/