The conversion from internal combustion engine (“ICE”) vehicles to electromobility is perhaps the most ambitious and largest world-wide public-private sector collaboration not prompted by a world war. It will have an extraordinary impact on the day-to-day mobility of millions of citizens on all continents who are dependent on personal vehicles, as well certain segments of those who rely on public mass transportation. The United States, along with vehicle manufacturers, set the ambitious target that half of all new US vehicle sales are to be electric by 2030. General Motors aims to deliver 400,000 EVs in North America by the end of 2023, and Ford has committed to 600,000 by that same time. Some countries, states and manufacturers have established even more aggressive timetables. For example, Volvo has announced it intends to be “all electric” by 2030.[i] Others like Toyota have targeted 2035, but plan to still offer hybrids.[ii]

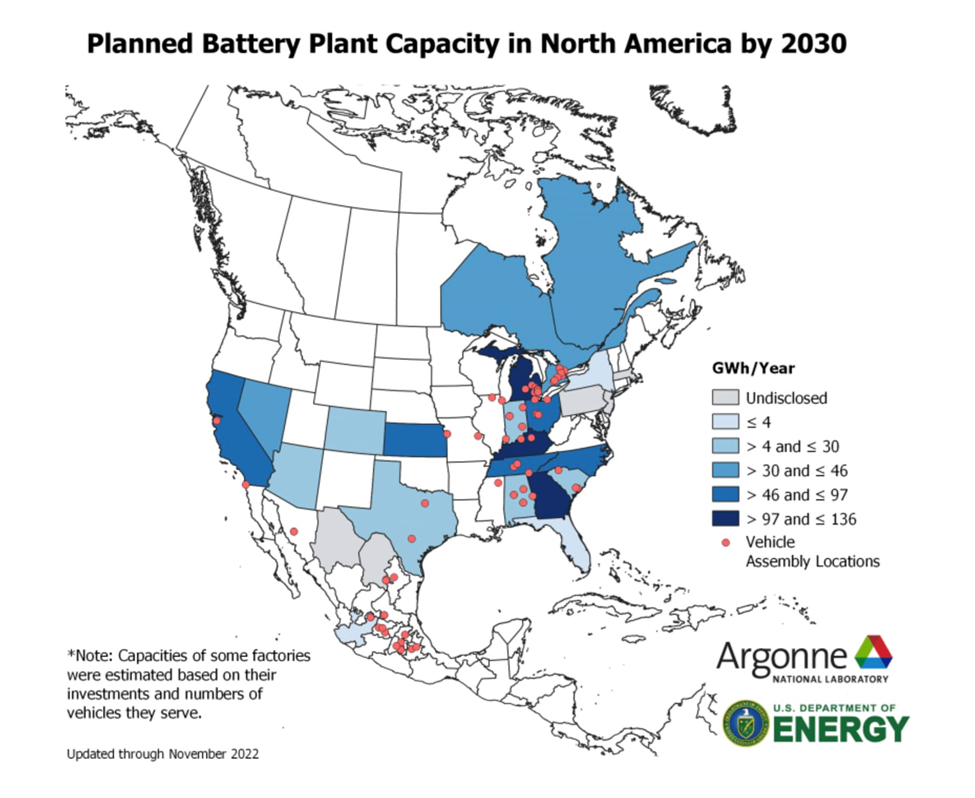

Automotive manufacturers, often in joint enterprises with other entities, are not only ramping up design and production of electrical vehicles (EVs)[iii] but also building battery manufacturing facilities in order to improve the supply chain necessary to have the batteries they will need. The biggest winners in efforts to increase battery manufacturing in the US will be Georgia, Kentucky, and Michigan along with Kansas, North Carolina, Ohio and Tennessee. (See Table A) It is reported that this represents a $40 billion investment with the prediction that these facilities will support the manufacturing of between 10 and 13 million all-electric vehicles per year. Similar cooperative efforts increase availability of batteries are underway in Europe.[iv]

Auto manufacturers are also creating strategic partnerships to create and support the necessary charging infrastructure. The need for high voltage charging points into homes and public spaces is universally recognized to be beyond the scope of what the automotive industry can accomplish alone. In the U.S. this resulted in passage of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) which includes $5 billion for EV charging infrastructure to states and another $2.5 billion in competitive grants for alternative fuel infrastructure. Some predict that to support electric vehicles in the United States in 2030, public and workplace charging will need to grow from approximately 216,000 chargers in 2020 to 2.4 million by 2030, including 1.3 million workplace, 900,000 public Level 2, and 180,000 direct current fast chargers.[v]

On February 15, 2023 the US issued long-awaited final rules on its national electric vehicle charger network that require the chargers to be built in the United States immediately, and with 55% of their cost coming from U.S.-made components by 2024.[vi] Companies that want to take advantage of federal funding for this network must also adopt the dominant U.S. standard for charging connectors, known as “Combined Charging System” or CCS; use standardized payment options; a single method of identification that works across all chargers; and work 97% of the time. This announcement coincides with Tesla’s statement that by late 2024 it will open 3,500 new and existing Superchargers along highway corridors to non-Tesla customers, and that it will also offer 4,000 slower chargers at locations like hotels and restaurants.[vii]

The European EV Charging Infrastructure Masterplan estimates that by 2030, approximately €280 billion will need to be invested by the 27 member countries in installing charging points (hardware and labor), upgrading the power grid, and building capacity for renewable energy production for EV charging. The European Union Parliament voted in October 2022 to require member states to build EV charging points at least every 60km on main motorways. If the parliament’s position is agreed with other EU institutions, countries would have until 2026 to reach this target. The UK’s energy regulator, in the meantime, has approved a £300 million investment to triple the number of ultra-fast electric charging points across the country. Private industry has responded by investing tens of millions in new manufacturing facilities to build the charging stations necessary to provide the infrastructure for mass use of EVs.[viii]

Impact on Retail and Hospitality

The retail and hospitality industry including traditional refueling stations, convenience stores, grocery stores, restaurants, malls, and hotels are seeing the benefits of installing charging stations and have already made commitments to make them available to customers.

Hotels

Multiple hotel chains including Holiday Inn, Best Western, Hilton, Marriott and Radisson have committed to installation of charging stations for the convenience of EV owners.[ix] Many have taken advantage of Tesla’s offer to have Destination Charging Stations installed at no cost which also allows them the opportunity to offer free charging to their customers. In the U.S., Radisson promotes its participation in the Destination Charing network stating “Whether you are staying for a weekend, for the night or just having dinner and drinks at one of our restaurants, be our guest and recharge your car for free, while you recharge yourself.”[x] In Europe, Radisson Hotel Group has grown its Green Mobility network of ultra-fast and regular (AC) charging solutions for electric vehicles to more than 220 locations and more than 510 chargers.[xi]

Marriott’s website includes a state-by-state listing of hotels with EV charging stations.[xii] In December 2022, Best Western announced selection of Imperalis Holding Corp., to be renamed TurnOnGreen Inc., as an endorsed supplier of electric vehicle charging systems for their North American properties. [xiii] The Hilton website identifies 1103 hotels as having EV charging stations.[xiv] The website “Stayncharge” identifies 1,293 hotels with charging stations.[xv]

Refueling and Convenience Stores

In 2021, TravelCenters of America, a full-service travel center network founded in 1972, formed a new business unit, eTA, “to deliver sustainable and alternative energy to the marketplace and focus on partnering with the public sector, private companies and customers to facilitate industry transformation.”[xvi] More recently, it announced an agreement with Electrify America to offer approximately 1,000 individual chargers (with an output of up to 350 kilowatts) at 200 locations along major highways over five years by 2028.[xvii] On February 16, 2023 it was announced that BP is acquiring TravelCenters of America Inc. (TA) in a deal valued at approximately $1.3 billion.[xviii]This coincides with an announcement by BP that it plans to invest $1 billion in EV charging across US by 2030. It currently offers 22,000 EV charge points worldwide and aims for more than 100,000 globally by 2030 with approximately 90% being rapid or ultra-fast chargers.[xix]

Buc-ee’s has contracted with Tesla to install Tesla Superchargers at 26 different Buc-ee’s locations across seven states. GM and Pilot Company (Pilot and Flying J) are collaborating on a national DC fast charging network that will be installed, operated and maintained by EVgo through its eXtend offering. This network of 2,000 charging stalls, co-branded “Pilot Flying J” and “Ultium Charge 360”, will be powered by EVgo eXtend and open to all EV brands at up to 500 Pilot and Flying J travel centers. GM customers will receive special benefits like exclusive reservations, discounts on charging, a streamlined charging process through Plug and Charge and integration into GM’s vehicle brand apps providing real-time charger availability and help with route planning.[xx]

Meanwhile, 7-11 advertises the availability of “7Charge” as

…a network of publicly available, EV fast chargers owned and operated by 7-Eleven at our stores. Backed by 100% green electricity, our chargers are located on often-traveled corridors, in well-lit store locations that are staffed 24 hours, 7 days a week by our friendly store personnel. Paying for charging is easy via the 7Charge app or by credit card at the charger. 7-Eleven makes EV charging convenient. As we deploy 7Charge across North America, we aim to be your #1 choice for convenient EV charging!” [xxi]

Circle K, (Alimentation Couche-Tard) which has over 14,000 stores in 24 countries including 7,008 company-operated convenience stores in 47 states, is deploying Circle K electric vehicle (EV) fast chargers to the United States with plans to bring the charging units to 200 Circle K and Couche-Tard convenience stores across North America over the next two years.[xxii]

Shell Oil has announced commitment to installation of 500,000 charging stations at existing stores by 2025 and 2.5 million by 2030. ABB[xxiii] will provide an end-to-end portfolio of AC and DC charging stations for the Shell charging network on a global and high, but undisclosed scale.[xxiv] Shell also opened a pilot EV charging hub in Fulham, England where petrol and diesel pumps at an existing fuel station were completely replaced with ultra-rapid charge points. [xxv] The hub includes a comfortable seating area, free Wi-Fi, a Costa Coffee cafe and an extensive Little Waitrose & Partners supermarket with a canopy that is built from sheets of timber, solar panels built into the canopy and the roof and shop from double glazing with high insulating properties In January 2021, Shell acquired ubitricity which provides EV charging through lamp posts.[xxvi]

FreeWire Technologies, a provider of battery-integrated EV charging stations and energy management solutions, has partnered with Chevron, Texaco and Phillips 66 to install EV chargers.[xxvii]

Supermarkets and “Big Box” Retail

In June 2022, Kroger, America’s largest grocery retailer, announced customers will have increased access to electric vehicle (EV) charging stations at certain locations. The grocer tested and phased in charger installations by collaborating with Blink, Electrify America, EVgo, Tesla and Volta to bring hundreds of charging stations to stores in Arizona, California, Colorado, Georgia, Indiana, Nevada, Oregon, Texas, Utah and Wyoming, with several more chargers expected to be installed by the end of the 2022. Future locations include Ohio, Illinois, Kentucky, Michigan, Tennessee and Virginia.[xxviii]

Electrify America, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Volkswagen Group of America, has partnered with Walmart to provide more than 120 superchargers at Walmart locations in 34 states.[xxix] Target has partnered with Electrify America, Chargepoint, and Tesla to bring both Level 2 and Level 3 charging options to more and more locations at a rapid rate and reportedly allow free charging for two hours and charge a fee beyond that (typically $2 dollars per hour).[xxx] Meijer says that it has charging stations at 20% of its stores, two offices and a distribution center. Publix’ website represents that it has chargers at 33 stores and “these easy to use chargers allow customers to charge their vehicles for free while they shop.” Home Depot, Costco and Safeway(Albertsons) [xxxi] are just a few others that have charging stations at many stores.

Rental Car Companies

The $56-billion U.S. rental car industry buys about one-tenth of auto manufacturers’ new cars every year and has made major investments in conversion of their fleets to EVs. Enterprise Holdings, which owns and operates Enterprise Rent-A-Car as well as the Alamo Rent A Car and National Car Rental brands offered EVs for rental in 2011 following its announcement in 2010 of the purchase of 500 Nissan LEAFs. It has subsequently added EVs from Tesla, Nissan, Hyundai and Volvo Cars spin-off Polestar to its fleet of 1.85m cars.[xxxii] Enterprise Fleet Management is partnering with Dominos to roll out a nationwide fleet of 800 custom-branded 2023 Chevy Bolt electric vehicles. In 2021 Hertz announced plans to purchase 100,000 Teslas followed by announcements to buy 65,000 Polestars and 175,000 Chevrolet, Buick, GMC, Cadillac and BrightDrop EVs over the next five years.[xxxiii] One of the issues rental car companies are dealing with is the impact of charging time on the turn-around time for rental of a vehicle after its return.[xxxiv]

How EV Users Find Chargers

Manufacturers like Tesla build in a program that helps drivers locate the nearest chargers. Popular apps include ChargeHub, Plugshare, Chargeway,Electrify America and EVgo.[xxxv] Several major refueling retailers have their own apps that will help loyal customers locate their chargers.

Risk and Liability Issues for Hospitality and Retail

The insurance industry has identified the following as potential risks of a loss with respect to EVs: Safety and reliability, fires, battery issues, environmental impact, speed to market issues, new supply chain exposures and cybersecurity.[xxxvi] Many of those risks fall primarily on the EV manufacturer, but fires that occur while a vehicle is charging and cyber breaches related to connectivity while charging brings premises owners, charger manufacturers and installers and potentially others well within the circle of entities likely to be brought into litigation.

To understand the potential exposure, one must understand the basics of the technology involved. With respect to charging stations it is important to understand the difference between networked and non-networked charging stations and the three main types of chargers.

Networked vs Non-Networked Charging Stations

Networked charging stations are connected remotely to a larger network and are part of an infrastructure system of connected chargers. As such, the chargers have remote access to online management tools through an online portal known as an EVSE network and you can locate them via various apps that can be downloaded to your phone and car navigation systems. In comparison, non-networked charging stations are stand-alone units that are not part of an EVSE network. Due to the fact that they are not connected to a network infrastructure, they are not accessible remotely. Since non-networked stations do not access internet systems, they do not have the ability to charge a fee for usage. This means that if you install a non-networked EV charger, you will be committing to providing free charging to anyone who plugs in. You will be unable to monitor usage and only be able to see the total electricity consumed by the unit in a given period of time. They are usually Level 2 chargers. An example of this type of charger are those manufactured by ClipperCreek which does not offer WiFi-connected smart chargers.[xxxvii]

An advantage of non-networked chargers is that they are much less expensive to install, eliminate some of the reliability issues and deprive hackers of an opportunity for mischief. A business can install several multiple Level 2 chargers for the price of one Level 3 fast charger. Plug In America estimates that currently 60% of EV drivers will need chargers at work, either because of longer commute distances or lack of access to at-home charging. [xxxviii] Employees who work at companies that have a workplace charging program are reported to be six times more likely to drive an EV than the average worker.[xxxix] This is a relatively inexpensive benefit to offer to employees that is effective, improves employee retention, and supports existing sustainability initiatives. Some Level 2 stations enable easier sharing with multiple connectors that allow vehicles to charge in succession without owners having to disconnect or move vehicles. A disadvantage of a non-networked charger is that they will not show up on the popular apps if availability is something you want to promote.

Types of EV Charging Stations

The types or categories of charging stations that can be effectively used by an EV owner is linked to the car’s charging capacity as well as the charger’s capacity, i.e. how much power it can provide. Broadly speaking, there are 3 types of connected charging stations that are widely used with a fourth, wireless charging, being touted as having a bigger role in the future.[xl]

Level 1 chargers are the slowest, most common type. They can be connected to a wall socket at home and deliver up to 2.3 kWh, or around 6 to 8 km of range per hour. The average cost is $379-$495. According to a 3-year study by the U.S. Department of Energy, 80% of EV charging happens at home.[xli]

Level 2 chargers provide higher speeds but require professional installation. They are the most common type found in residential, commercial, and municipal settings. Most level 2 chargers can deliver at least 7.4 kWh or 11 kWh, with some capable of up to 22 kWh. Charging on those power outputs adds about 40 km, 60 km, and 120 km per hour respectively. The average cost is $329-$2700.

Level 3 chargers, also called DC or fast chargers, can deliver the most power and highest charging speed. They require bulky transformers and are not cost-effective for residential and most municipal uses. The highest-rated level 3 chargers can deliver up to 350 kWh, although lower outputs such as 50 kWh, 125 kWh, and 150 kWh are more common. At those rates, most EVs can charge up to 80% in less than an hour, sometimes even as little as a few minutes. While they are expensive to install, commercial DC Fast Chargers for electric vehicles offer many benefits and are a great choice for some commercial properties including office buildings, large shopping malls, retail centers, and more. According to a study from the International Council on Clean Transportation, DC Fast Chargers (DCFC) cost approximately $28,000 to $140,000 per unit installed.

It is important to know that weather conditions, particularly temperature, can impact charging speed. Batteries have a narrow optimal operating range of around 21°C. When the temperatures are significantly higher or lower, the battery will use some energy to heat or cool itself, increasing the time it takes to charge it. There are manufacturers of solar powered Level 2 chargers that claim faster charging times.[xlii] The General Services Administration has contracted to install solar powered chargers at 140 solar-powered electric vehicle charging stations at 34 sites around the country.[xliii] The federal fleet consists of more than 423,000 leased and agency-owned vehicles with the number of ZEVs ordered by GSA for the federal fleet rising from 643 in FY21 to more than 3,550 in FY22.

Wireless charging: A fourth type of charging in the developmental stage is wireless charging. Momentum Dynamics, which has been commercializing fully automated inductive (wireless) charging for electric vehicles (EVs) since 2014.[xliv] Technology group MAHLE and electronics giant Siemens have signed a declaration of intent to collaborate on wireless charging systems for EVs.[xlv] Another company in this field is InductEV.[xlvi]

Safety and Reliability

Although there are electrical standards applicable to charging stations that minimize the risks associated with use of electricity, all networked stations depend on connectivity between the user and the charger and the charger to payment systems. A 2022 survey in California, the state with the most EVs in use, revealed that a total of 22.7% of connectors were non-functioning due to problems including network connectivity issues, broken plugs, unresponsive screens, and payment system failures. Around 5% of connectors had cables that were too short to reach an EV’s charging port, rendering them unusable.[xlvii] A J.D. Power survey reported in August 2022 yielded similar findings in that 20 percent of respondents who went to a public charging station did not charge their vehicle. The reason cited by 72 percent of those who didn’t charge was that the station was somehow broken or out of service.[xlviii]

Fire Risks

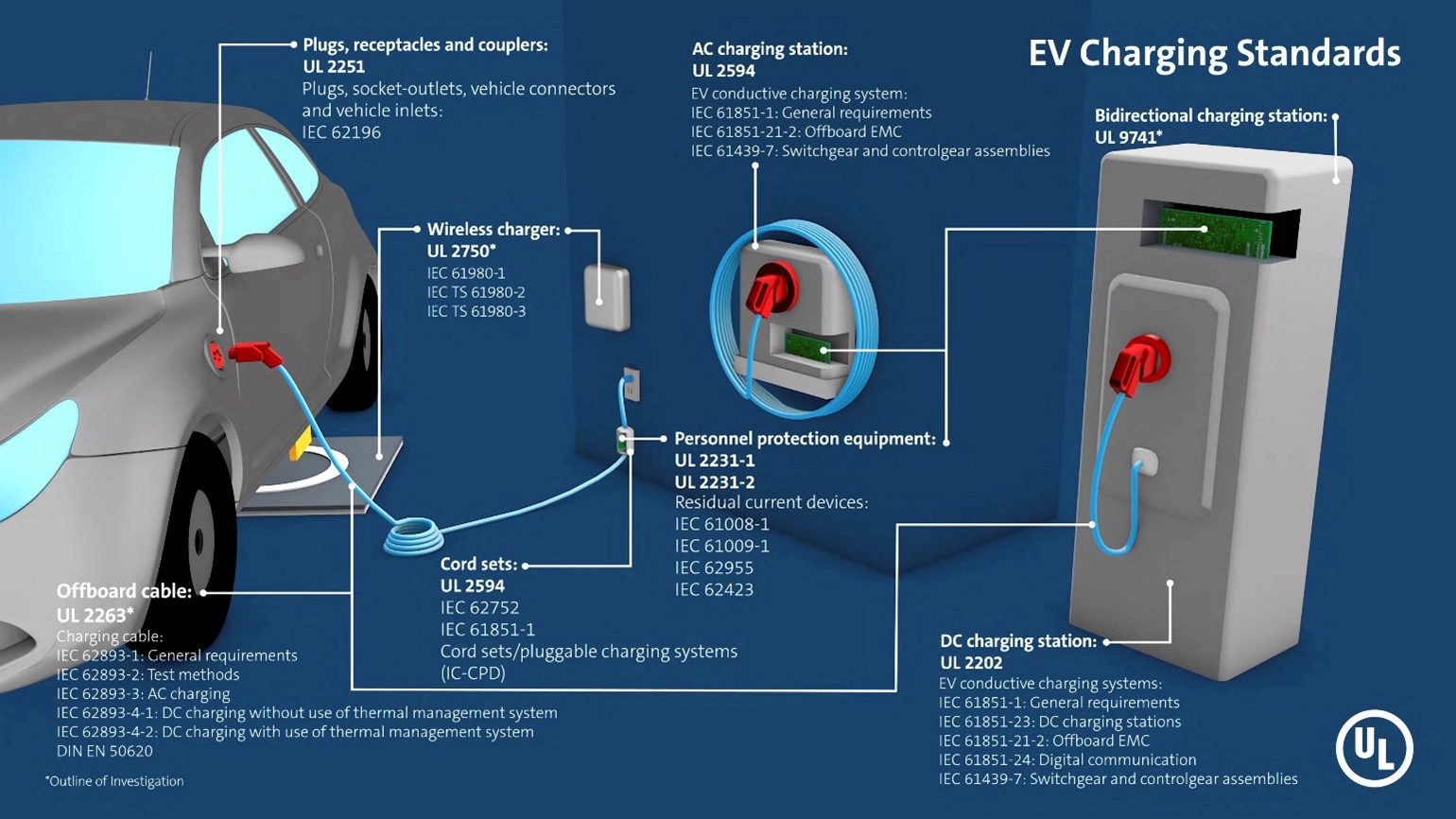

Although a few Tesla fires and concerns about Chevy Bolts have received a lot of media attention, the statistics show that you are more likely to have a fire from a hybrid vehicle or a gas powered vehicle than a BEV. Manufacturers have built-in precautions so you can’t overcharge, over-discharge, or overheat: the three biggest killers of battery longevity. EV chargers face the same fire risk as any electrical installation, but there are standards that if adhered to minimize the risk. (See Table B) The safety of the charging stations can be affected by wiring components as well as the competency and experience of the installer. Improper or outdated wiring can short circuit, arc, and/or overheat, all of which can result in a serious fire.

Technical faults and manufacturing defects of batteries can indeed lead them to catch fire. However, the cases are also due to personal negligence and not taking proper precautions. Most EV battery fires occur when the battery is damaged or punctured. That said, the nature and characteristics of a BEV fire are that they are much hotter, harder to extinguish, can reignite days later and are likely to destroy the vehicle. They also create hazards for those attempting to extinguish them. As stated by the NTSB[xlix]:

Fires in electric vehicles powered by high-voltage lithium-ion batteries pose the risk of electric shock to emergency responders from exposure to the high-voltage components of a damaged lithium-ion battery. A further risk is that damaged cells in the battery can experience uncontrolled increases in temperature and pressure (thermal runaway), which can lead to hazards such as battery reignition/fire. The risks of electric shock and battery reignition/fire arise from the “stranded” energy that remains in a damaged battery.

As a practical matter, a regular car, fully involved, would take less than 500 gallons of water which is within the storage capacity of many fire trucks, whereas electric vehicle fires, depending on how involved they are, can reportedly require anywhere from a thousand to several thousands of gallons of water to extinguish. The length of time the firefighters will need to be on the scene is much greater and, unless there are hydrants nearby, it will require multiple units to respond simply to provide the supply of water necessary.

If the premises owner is installing EV chargers in a parking garage or deck, there are special NFPA standards that are implicated. Planning should include review of the requirements in Article 625, Electric Vehicle Power Transfer System and NFPA 88A which lists UL standards that must be met such as UL 2202, Standard for Electric Vehicle (EV) Charging System Equipment and UL 2594 and UL 2750.

Cybersecurity

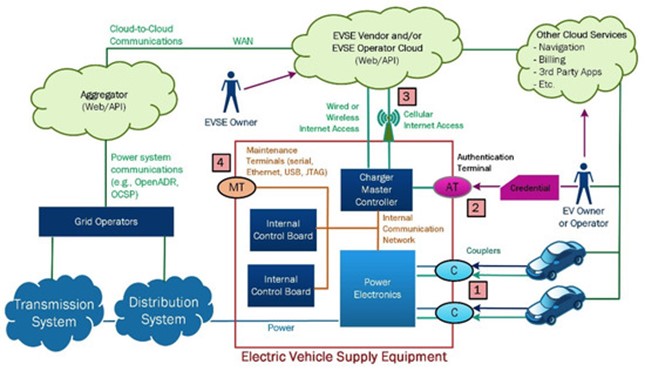

The evolution of connected and automated cars, intelligent infrastructure and the advancement of artificial intelligence and machine learning has placed cybersecurity in the heart of the risk assessment. Electric vehicle charging infrastructure has several vulnerabilities ranging from skimming credit card information — just like at conventional gas pumps or ATMs — to using cloud servers to hijack an entire electric vehicle charger network. The electric vehicle supply equipment infrastructure (EVSE) has multiple participants who are dependent on the cybersecurity of the EVSE. (See Table C) These participants have different cybersecurity interests and risk levels which should be considered in the design, installation, and use of EVSEs.

The parties involved may include:

- The vehicle owner/user who is recharging the vehicle

- The vehicle manufacturer

- The grid operator

- The charging station manufacturer

- The charging station owner

- Credit card company if used for payment purposes

- Building management systems

The implementation of an EVSE creates connections between sectors (transportation and electrical grid) that are not common in the current gasoline-powered vehicle environment. The researchers also agreed that new targets for attackers and the potential for new vulnerabilities have been created. Among the possible consequences discussed were:

- Disruption of electrical grids

- Safety-adverse effects on vehicles

- Credit card or banking fraud

- Interference with building systems

Most of the risks known by the public are due to the efforts of hackers with no malicious motive. For example, it was recently reported that a “white hat” hacker exposed potential vulnerabilities and security issues in Electrify America units by using a program known as TeamViewer. [l] He was able to navigate with a mouse, type on a keyboard, and get full access to the charger’s internal computer, which was reportedly wide open.

In 2020, Tesla announced it was offering $1-million and a free car to security researchers who found bugs in its systems. Not long thereafter, a 19 year old German IT security specialist and hacker, David Columbo, announced he was able to take control of 25 Teslas including disabling Sentry Mode, opening the doors/windows and even starting Keyless Driving. While working on another programming project for a French company, he examined the code that constituted a data logger that was being used by Tesla. The data logger shows where the Tesla has been driven, how fast, and other such usage statistics. In the process he discovered he could easily find out where the CEO of the French company was driving his own Tesla, along with other private information. He started reading source code from GitHub that went into other Tesla components. He then discovered that open source software stores the digital car keys in a way that could be accessed easily from the outside. There was no encryption and could easily obtain the digital car keys to any car. With control over the keys, he could remotely disable the car’s security mode, unlock the doors, honk the horn. If the owner’s garage door opener was connected to the car, he could open the garage door, too– all from his laptop in Germany. He could also query the exact location and see if a driver is present. The list is pretty long including the ability to remotely play music he chose on YouTube in their Teslas. However, he laid the fault on the owners/users rather than Tesla. He was able to do all of this by using a vulnerability in TeslaMate, a third-party API (application programming interfaces, which is basically software that allows applications to communicate) that some Tesla owners use to analyze data from their vehicle.

Limitations of Liability in User Agreements

All the major charging station providers such as Chargepoint, EVgo, Electrify America and Blink have Terms of Use agreements that include language that disclaims any warranties, limits their liability and, in some cases, that of the “host” of the unit(s) as well. For example, Electrify America’s TOU[li] states in its introductory paragraph:

IF YOU DO NOT AGREE WITH THIS TOU, YOU ARE NOT GRANTED PERMISSION TO ACCESS OR OTHERWISE USE THE SOLUTION OR ANY COMPONENT THEREOF, AND ARE INSTRUCTED TO EXIT THE APP IMMEDIATELY, AND/OR STOP YOUR USE OF THE NETWORK.

The EVgo TOU[lii] includes an Arbitration clause requiring the arbitration to be conducted in Los Angeles, California, waiver of the right to a jury trial and a clause limiting the users remedies as follows:

Exclusive Remedy

Your sole and exclusive remedy for any claim arising out of or relating to EVgo’s breach of these Terms or the terms of a Plan shall be for EVgo, upon receipt of written notice, to use commercially reasonable efforts to cure the breach at its expense or, at EVgo’s election, return the fees you paid to EVgo for the Services in the month during which the breach occurred, and, at EVgo’s option terminate the Plan

EVgo’s TOU caps damages:

…SHALL NOT IN THE AGGREGATE EXCEED THE TOTAL AMOUNT OF THE FEES PAID BY YOU WITH RESPECT TO THE SERVICES DURING THE SIX (6) MONTHS IMMEDIATELY PRIOR TO THE EVENT GIVING RISE TO THE LIABILITY.

Blink’s TOU also disclaims warranties, limits liability, has an indemnification clause and requires arbitration. It includes a procedure for opting out of arbitration but requires that by opting out of the Arbitration Agreement the user “expressly agree to submit to the jurisdiction and proper venue of the competent state or federal courts located in Miami-Dade County, Florida.”[liii]

The above are examples of language governing the use of charging stations by EV drivers. There will be separate agreements governing the obligations of the entity that manufactured and or installed the charging stations. One such agreement used by Chargepoint is available online. https://chargepoint.ent.box.com/v/CP-Purchase-Terms-Conditions It includes typical contract language including limitations of liability and an arbitration clause.

Is Electricity Provided to an EV Driver a Product, Good or Service

An issue that is potentially important to a premises owner making EV chargers available to customers, particularly if it is receiving compensation, is whether the transaction will be governed by the U.C.C., product liability law or general tort/premises liability principles. That determination will not only impact the substantive law, but the applicable statute of limitations. If it is a “good” or ”product” instead of a “service” the U.C.C. and potentially product liability law will govern. Absent some statutory governance, if it is a “service” then the court and parties will likely be looking to general tort and premises liability law to resolve the dispute. There is a split of authority depending on the venue. For example, in Otte v. Dayton Power & Light Co., 37 Ohio St. 3d 33, 523 N.E. 2d 835 (Ohio 1988) the court concluded that “… electricity is a service, not a product …” with the following analysis:

Consumers, moreover, do not pay for individual electrically charged particles. Rather, they pay for each kilowatt hour provided. Thus, consumers are charged for the length of time electricity flows through their electrical systems. They are not paying for individual products but for the privilege of using DP&L’s service.

It is also important to note that an electrical charge released by an electric company at a power plant is substantially different in several respects from the charge that ultimately enters one’s home. Section 402A(1)(b) of the Restatement requires that the product reach the consumer “without substantial change in the condition in which it is sold.” This condition precedent clearly has not come into play under the undisputed facts of the case at bar. As an appellate court noted in Rickert v. Dayton Power & Light Co. (Dec. 20, 1984), Darke App. No. 1105, unreported, the electrical charge that flows through a power line may have a charge as high as 7,200 watts. The electrical charge is reduced substantially before it enters one’s home. It is apparent that electric power cannot be considered a product intended to reach the consumer in the same condition in which it is released at a power plant. For this reason, and for the reasons stated above, we find electricity is a service, not a product, in the generally accepted sense of the word under the factual context of this case.

We must note that there are a scattering of cases that have determined electricity is a product for strict liability purposes. Some have reached the curious conclusion that electricity passing through a consumer’s meter becomes a product, but electricity not passing that point is a service. Although this distinction is convenient for Section 402A analysis purposes, we find it unsupported by both logic and common sense. The jurisdictions finding electricity to be a product with no meter distinction fail to recognize that electricity is not manufactured and that it undergoes a substantial change in form before entering the home. We decline the invitation to follow such logic.

The issue has arisen a number of times in bankruptcy litigation. For example, in In re NE Opco, Inc., 501 B.R. 233 (Bankr. D. Del. 2013the Court held :

Electricity is not a good under section 503(b)(9) of the Bankruptcy Code. In order for something to be a good under the U.C.C. and, thus, section 503(b)(9) of Bankruptcy Code, it must be movable at the time of identification to the contract for sale. Electricity is identified as it passes through a meter but it is almost immediately consumed. Indeed, the delay between identification and use is measured in microseconds. In order to do justice to the definition of a good, however, the separation of identification and consumption must be meaningful and, in the case of electricity, that infinitesimal “gap” is too short to establish that electricity is moveable at the time of identification. It is not and, as such, electricity is not a good.

See also, PacifiCorp v. N. Pac. Canners & Packers, Inc., 2023 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 18798. But, see In re Escalera Res. Co., 563 B.R. 336 (Bankr. D. Colo. 2017) for lengthy analysis of why that court believes the better reasoning is that electricity is a product, commodity and good rather than a service. It identified 22 States that expressly define “electricity” as “tangible personal property” in connection with state taxation.

States/Courts that have held electricity to be a “service” include:

Kentucky: G & K Dairy v. Princeton Elec. Plant Bd., 781 F. Supp. 485, 489 (W.D.Ky. 1991)

Massachusetts: New Balance Ath. Shoe v. Boston Edison Co., 1996 Mass. Super. LEXIS 496, 1996 WL 406673 (Mass.Super.Ct.1996)

Michigan: Williams v. Detroit Edison Co., 63 Mich.App. 559, 563, 234 N.W.2d 702 (Mich.Ct.App.1975); Buckeye Union Fire Ins. Co. v. Detroit Edison Co., 38 Mich.App. 325, 196 N.W.2d 316, 317 (1972);

Minnesota: ZumBerge v. Northern States Power Co., 481 N.W.2d 103, 108 (Minn. App. 1992)

Missouri: Balke v. Central Mo. Elec. Coop., 966 S.W.2d 15 (Mo. App. 1997)

New York: Bowen v. Niagara Mohawk Power Corp., 183 A.D.2d 293, 590 N.Y.S.2d 628, 631 (N.Y.A.D. 1992); ;United States v. Con. Edison Co., 590 F.Supp. 266, 269 (S.D.N.Y.1984

Wyoming: Wyrulec Co. v. Schutt, 866 P.2d 756, 760 (Wyo. 1993)

States/Courts holding that electricity is a “good” or product include identified in footnotes in In re Escalera Res. Co, supra.:

California: Pierce v. Pac. Gas & Elec. Co., 166 Cal.App.3d 68, 82-84, 212 Cal. Rptr. 283 (Cal. App. 1985) (electricity delivered in marketable state to customer is a “product”).

Colorado: Smith v. Home Light & Power Co., 695 P.2d 788, 789 (Colo. App. 1985) (“We agree that electricity itself is a product, but conclude that its distribution is a service.”), aff’d, 734 P.2d 1051 (Colo. 1987) (“at least until the electricity reaches a point where it is made available for consumer use, it is not a ‘product’ that has been ‘sold'”).

Connecticut: Travelers Indem. Co. of Am. v. Conn. Light & Power Co., 2008 Conn. Super. LEXIS 1387, 2008 WL 2447351, at *5 (Conn. Super. Ct. June 4, 2008) (“It is the opinion of this court that the electricity is a product for the purposes of [Connecticut law] once it passes through the meter of a consumer”).

Georgia: Monroe v. Savannah Elec. & Power Co., 219 Ga. App. 460, 465 S.E.2d 508, 510 (Ga. App. 1996) (“electricity may only be considered a product within the meaning of Georgia’s strict liability statute when it has been ‘sold’ or placed in the stream of commerce, i.e., the utility has placed the electricity in the hands of and under the control of a consumer”), aff’d, 267 Ga. 26, 471 S.E.2d 854, 855-56 (Ga. 1996) (“we concur with the rationale presented in the majority view and accordingly hold that electricity is product”).

Illinois: Elgin Airport Inn, Inc. v. Commonwealth Edison Co., 88 Ill. App. 3d 477, 410 N.E.2d 620, 624, 43 Ill. Dec. 620 (Ill. App. 1980) (“Having in mind that electrical energy is artificially manufactured, can be measured, bought and sold, changed in quantity or quality, delivered whenever desired and has been held . . . to be personal property [that can be stolen], we are of the opinion that it is a product . . . .”), aff’d in part and rev’d in part on other grounds, 89 Ill. 2d 138, 432 N.E.2d 259, 59 Ill. Dec. 675 (Ill. 1982).

Indiana: Hedges v. Pub. Serv. Co. of Indiana, 396 N.E.2d 933, (Ind. App. 1979) (metered electricity sold in consumer voltage and passed into the household system is a “good” covered by the UCC, while raw electrical energy encountered in an unmarketed and unmarketable state in an overhead transmission cable was not)

Pennsylvania: Cincinnati Ins. Co. v. PPL Corp., 979 F. Supp. 2d 602, 609-10 (E.D. Pa. 2013) (electricity is a “product” under Restatement Section 402A after it passes through the customer’s meter); Schriner v. Pa. Power & Light Co., 348 Pa. Super. 177, 501 A.2d 1128, 1134 (Pa. Super. Ct. 1985) (“electricity only becomes a product, for purposes of strict liability, once it passes through the customer’s meter and into the stream of commerce”).

Texas: Houston Lighting & Power Co. v. Reynolds, 765 S.W.2d 784, 785 (Tex. 1988) (“We agree with the better reasoned opinions of other jurisdictions which hold electricity to be a product. Electricity is a commodity, which, like other goods, can be manufactured, transported and sold . . . Electricity is a form of energy that can be made or produced by man, confined, controlled, transmitted and distributed to be used as an energy source for heat, power and light.”); Hanus v. Tex. Util. Co., 71 S.W.3d. 874, 878 (Tex. App. 2002) (“Because it is a commodity that can be manufactured, transported, and sold like other goods, electricity is considered a product for strict liability purposes after it has been converted, as it had been here, to a form usable by consumers.”).

Wisconsin: Ransome v. Wis. Elec. Power Co., 87 Wis. 2d 605, 625, 275 N.W.2d 641 (1979)( electricity is a product that subject to principles of strict liability in appropriate cases; evidence unequivocally led to a finding that the electricity was in such a defective condition as to be unreasonably dangerous to the homeowners when it left the electric company’s possession.)

Potential Insurance Issues

The risks associated with making charging stations available warrants a closer look at the insurance coverage a retail or hospitality entity carries. To mitigate future risk, policyholders should review their CGL policies and any stand-alone cyber policies with experienced counsel to determine whether there is a gap in their coverage. Review what information was provided to the broker and carrier about your operations and make sure they are on notice that you just installed a bank of networked EV chargers the availability of which is being advertised on your website and via multiple apps EV owners use. Consider that charging stations situated on the property remote from the primary building and available 24 hours a day create different risks than having an open parking lot with no reason to be there afterhours. A Tesla driver charging a vehicle at 2:00am is probably just as much an invitee as the person buying groceries at 7:00pm. Make sure that the lighting you use elsewhere for customers is equally as illuminating at the charger locations.

Table A

EV Charging Standards

Table B

Table C

Electric Vehicle Charger Cybersecurity Vulnerabilities[liv]

Endnotes

[i] https://www.cnbc.com/2021/03/02/volvo-says-it-will-be-fully-electric-by-2030-move-car-sales-online.html

[ii] https://www.cnbc.com/2022/09/13/why-toyota-the-worlds-largest-automaker-isnt-all-in-on-evs.html

[iii] For example, Mercedes-Benz will begin to assemble electric SUVs at its Tuscaloosa plant in 2022 and is investing $1 billion to construct an EV battery plant in Bibb County, Alabama. In May 2021, Hyundai, which has a manufacturing plant in Montgomery, Alabama unveiled a plan to invest $7.4 billion in the U.S. by 2025.

[iv] https://chargedevs.com/newswire/total-saft-and-groupe-psa-opel-to-launch-pilot-plant-for-battery-production/

[v] https://theicct.org/publication/charging-up-america-assessing-the-growing-need-for-u-s-charging-infrastructure-through-2030/

[vi] https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/new-biden-ev-charger-rules-stress-made-america-force-tesla-changes-2023-02-15/

[vii] https://www.reuters.com/technology/tesla-open-us-charging-network-rivals-75-bln-federal-program-white-house-2023-02-15/

[viii] For example, ABB recently announced a multi-million dollar investment in a Columbia, South Carolina factory that will increase production of electric vehicle chargers, including ones that are Buy America Act compliant. https://new.abb.com/news/detail/94725/abb-expands-us-manufacturing-footprint-with-investment-in-new-ev-charger-facility

[ix] https://electriccitycorp.com/hotels-with-ev-charging/

[x] https://www.radissonhotels.com/en-us/partner/tesla

[xi] https://hotelbusiness.com/radisson-hotel-group-launches-its-first-electric-charging-hub/

[xii] https://help.marriott.com/s/article/Article-33854

[xiii] https://ngtnews.com/best-western-picks-turnongreen-as-ev-charger-supplier-for-hotels-and-resorts

[xiv] https://www.hilton.com/en/locations/usa/ev-charging/

[xv] https://www.stayncharge.com/search_results

[xvi] https://www.ta-petro.com/newsroom/travelcenters-of-america-enhances-commitment–to-sustainability-and-alternative-en

[xvii] https://insideevs.com/news/651602/1000-fast-chargers-travelcenters-electrify-america/

[xviii] https://www.csnews.com/bp-acquire-travelcenters-america-13b

[xix] https://www.bp.com/en_us/united-states/home/news/press-releases/bp-plans-to-invest-1-billion-in-ev-charging-across-us-by-2030-helping-to-meet-demand-from-hertzs-expanding-ev-rentals.html

[xx] https://pilotflyingj.com/press-release/19335

[xxi] https://www.7-eleven.com/7charge

[xxii] https://www.csnews.com/couche-tard-begins-rolling-out-circle-k-ev-fast-chargers

[xxiii] ABB manufactures what they claim is the fastest of the DC fast chargers, the Terra 360 with an output of 360 kW that is most appropriate for refueling stations, urban charging stations, retail parking and fleet applications and has a new manufacturing facility in South Carolina.

[xxiv] . https://insideevs.com/news/582885/abb-shell-global-framework-agreement-charging/

[xxv] https://www.shell.com/energy-and-innovation/mobility/electric-vehicle-charging.html

[xxvi] https://www.shell.com/energy-and-innovation/mobility/mobility-news/shells-growing-public-ev-charging-network.html

[xxvii] https://chargedevs.com/?s=FreeWire+

[xxviii] https://ir.kroger.com/CorporateProfile/press-releases/press-release/2022/Kroger-Expands-Customer-Access-to-Electric-Vehicle-Charging-Stations/default.aspx

[xxix] https://corporate.walmart.com/newsroom/2019/06/06/electrify-america-walmart-announce-completion-of-over-120-charging-stations-at-walmart-stores-nationwide-with-plans-for-further-expansion

[xxx] https://homebatterybank.com/charging-an-ev-at-target-where-cost-how-long/;

[xxxi] https://progressivegrocer.com/safeway-installs-another-electric-vehicle-charging-station

[xxxii] https://www.ft.com/content/c20e4f4b-1a6e-4b51-a38c-97783e75a847

[xxxiii] https://electrek.co/2022/09/20/hertz-massive-order-175000-electric-vehicles-gm/#:~:text=Last%20year%2C%20Hertz%20announced%20an,100%2C000%20Tesla%20Model%203%20vehicles.

[xxxiv] https://www.ft.com/content/c20e4f4b-1a6e-4b51-a38c-97783e75a847

[xxxv] https://www.makeuseof.com/best-electric-vehicle-charging-station-apps/

[xxxvi] The electric vehicles r-ev-olution: Future risk and insurance implications, https://www.agcs.allianz.com/news-and-insights/reports/electric-vehicles.html

[xxxvii] https://clippercreek.com/

[xxxviii] https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2017/01/f34/WPCC_2016%20Annual%20Progress%20Report.pdf

[xxxix] https://pluginamerica.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/PIA-MA-Workplace-Charging-Guide-Report.pdf

[xl] https://www.reviewgeek.com/131974/the-future-of-wireless-ev-charging-already-exists/#:~:text=So%20how%20does%20that%20work,battery%20to%20power%20an%20EV.

[xli] https://avt.inl.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/arra/PluggedInSummaryReport.pdf

[xlii] https://www.solaredge.com/us/ev-charger

[xliii] https://www.gsa.gov/about-us/newsroom/news-releases/gsa-and-va-bring-solarpowered-ev-charging-stations-nationwide-10072022

[xliv] https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/momentum-dynamics-announces-dual-power-breakthrough-in-automatic-inductive-charging-301540373.html

[xlv] https://chargedevs.com/newswire/mahle-and-siemens-cooperate-to-develop-wireless-charging/

[xlvi] https://www.inductev.com/home#use-cases

[xlvii] https://www.businessinsider.com/electric-car-charging-reliability-broken-stations-ev-2022-5

[xlviii] https://www.jdpower.com/cars/shopping-guides/ev-drivers-less-satisfied-with-public-charging

[xlix] https://www.ntsb.gov/safety/safety-studies/Pages/HWY19SP002.aspx

[l] “Electrify America Charging Stations Vulnerable To Hacking” https://insideevs.com/news/642914/electrify-america-charging-station-bugs-easy-hacking/

[li] https://www.electrifyamerica.com/terms/

[lii] https://www.evgo.com/terms-of-service/

[liii] https://blinkcharging.com/terms-conditions/

[liv] See Review of Electric Vehicle Charger Cybersecurity Vulnerabilities, Potential Impacts, and Defenses, Energies 2022, 15(11), 3931; https://doi.org/10.3390/en15113931 or https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1073/15/11/3931