Protecting Websites from Copying

There are several legal avenues that a company can pursue to protect its website from unlawful copying by competitors. Federal copyright law protects the content of a website. Statutory protections against trademark infringement prohibit the use of a domain name that is confusingly similar to another company’s trademark. And the legal doctrine of trade dress exists to prevent competitors from copying or imitating the design and appearance of a website. The type of unlawful conduct presented will inform which avenue the company should take.

A. Copyright Infringement

Copyright infringement is the unauthorized use of another individual or entity’s existing copyrighted work, such as photographs, illustrations, videos, or other graphic images. Copyright infringement is a growing problem with thousands of online scammers using stolen copyright content on their commercial websites to fool consumers online, potentially damaging the sales and reputation of the company whose content has been stolen. For this reason, it is essential for a company to immediately take action against a website for copyright infringement upon discovering that their content has been stolen.

The easiest route to remove the content is to file a Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) Takedown Request with the infringer’s web host. Since its enactment in 1998, the DMCA requires each web host to designate an agent to receive and process Takedown Requests, thus providing a quick mechanism to file a complaint – without the need to engage outside counsel. Pursuant to the DMCA, web hosts must expeditiously remove infringing content upon notification.

The first step before initiating a DMCA Takedown Request is to gather the relevant information. There are websites that you can use to ascertain the IP address of the infringing website and the identity of the web host that is hosting the infringing website. (One such website is whois.domaintools.com). It is imperative when filing a Takedown Request that the host be based in the United States. Copyright law is country-specific. The DMCA only applies to United States hosted websites. So, if a host is in another country, the Takedown Request may not work. Still, it might be prudent to send a letter, and, if possible, advance other theories (i.e., fraud, trademark infringement, etc.).

A DMCA Takedown Request must also meet certain criteria. To wit:

- Specification of Copyrighted Content. The Request must identify the work that is claimed to be copyrighted and infringed, or, if there are multiple copyrighted works at a single online site, a representative list of such works.

- Location of Infringing Material. The Request must also identify the material that is claimed to be infringing, and must provide information sufficient to permit the IP host to locate the material. This must include the specific URLs for each infringing instance.

- Contact Information for the Complaining Party. The Request must provide information reasonably sufficient to permit the IP host to contact the complaining party, such as a full personal name, address, and telephone number, as well as facsimile number and email, if available, at which the complaining party may be contacted.

- Good Faith Statement. The Request must include an explicit statement that the complaining party has a good faith belief that the use of the material in the manner complained of is not authorized by the copyright owner, its agent, or the law.

- Statement Under Perjury. The Request must include a statement that the information in the notification is accurate, and that the complaining party is authorized to act on behalf of the copyright owner of an exclusive right that is allegedly being infringed.

- Signature. Finally, the Request must contain a physical or electronic signature of the complaining party or its agent.

Even a fully compliant Takedown Request, however, may be met with no response or even a denial from the IP host. In this scenario, your options are somewhat limited. You should follow up with the IP host to prod them and/or to learn why they rejected the Takedown Request.

Unfortunately, even when the IP host grants the Takedown Request, and removes or suspends the offending material, the problem may not be over. Rather, as what can only be described as akin to “whack a mole,” the online scammer may simply move the offending material to another IP host and thus the website with infringing content will reappear. It is thus imperative to continuously monitor offending material, even after the IP host has taken it down.

B. Domain Name Infringement

A more permanent solution may be obtained through the Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy (“UDRP”) process, which is a streamlined arbitration process that specifically addresses domain name disputes. This process may only be utilized, however, where there is an infringing domain name. Indeed, when a person or entity registers a domain name, the registration agreement typically requires that the registrant represent that registering the domain will not infringe upon or otherwise violate the rights of any third party, and requires the registrant to participate in a UDRP arbitration if any third party asserts such a claim.

A UDRP complainant must establish three elements: (1) the domain name is identical or confusingly similar to a trademark in which the complainant has rights; (2) the domain name registrant does not have any rights or legitimate interests in the domain name; and (3) the domain name has been registered and is being used in “bad faith.” There are several non-exclusive factors that will be considered in assessing “bad faith,” including whether the registrant acquired the domain name to attract, for commercial gain, internet users to its web site by creating a likelihood of confusion with the complainant’s mark.

The UDRP process itself involves filing a complaint with one of the UDRP providers—typically, either the World Intellectual Property Organization (“WIPO”) or the National Arbitration Forum (“NAF”). The domain name registrant may file a response and each party may potentially be permitted to file one additional submission. There is no discovery and no in-person hearing. Rather, the panel appointed by the UDRP provider decides the dispute based on the pleadings alone. The panel may be one or three individuals (the parties have the choice) selected from a specified pool of trademark law practitioners, former judges and arbitrators who meet certain criteria.

It is fairly common in these types of cases that the domain name registrant will not even file a response to the UDRP complaint. A default by the domain name registrant does not, however, result in an automatic win for the complainant. Rather, UDRP panelists will analyze the merits of the complaint, even if no response is filed (although a panelist may draw appropriate inferences from the registrant’s failure to respond). For these reasons, UDRPs are limited to clear cases of bad-faith, abusive registration. Complex trademark or contractual disputes, for example, are outside the scope of the UDRP.

The remedies offered by the UDRP are narrow and are limited to either cancellation or transfer of the domain name. No damages are awarded and no injunctions issue. Any party that loses a UDRP proceeding may, however, still file a lawsuit, as UDRP actions are not binding on the court. The UDRP is, however, a much less costly and expeditious alternative to litigation. The cost is approximately between $1,300 and $1,500 (excluding any legal fees) and typically the matter resolves within about 60 days.

One word of caution: if a company files a UDRP complaint, but clearly should have known it could not prevail, the panel may find reverse domain name hijacking. Such a finding may complicate subsequent UDRP efforts by the company. Further, a complainant’s knowing and material misrepresentations in a UDRP may create a cause of action for damages, costs, and attorneys’ fees under the Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act.

C. Trade Dress Copying

The content of a company’s website and its domain name are not the only potentially protected aspects of the website. Indeed, the statutory and decisional law governing trade dress further protects companies from the copying or imitating of the design and appearance of their website. Trade dress protects the overall image of a product, its packaging, stores, restaurants – and in the right circumstances, a website — from improper copying. Think of the iconic Coca-Cola bottle, the shape and colors of IHOP restaurants, the combination of colors and designs of Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups. Such protection ensures that customers can reliably identify a particular business by the overall look and feel of the commercial interior. In other words, it protects the affiliation in the consumer’s mind between a specific interior design scheme and a commercial source.

Websites are in many ways equivalent to old-fashioned storefronts in today’s commercial environment. Trade dress therefore provides the most logical basis of intellectual property protection for the look and feel of a website. In a recent case, the U.S. District Court for the District of Connecticut addressed trade dress infringement claims under the Lanham Act arising from website copying. Graduation Solutions, LLC v. Acadima, LLC, 2020 WL 1466204, at *1 (D. Conn. Mar. 26, 2020). In Graduation Solutions, both parties designed and sold graduation apparel and accessories through their own websites. Id. at *1. Graduation Solutions filed a complaint against Acadima alleging trade dress infringement and other causes of action on the grounds that Acadima owned and controlled websites that essentially copied Graduation Solutions’s website. Id. Graduation Solutions claimed that its customers were confused and sought injunctive relief, compensatory damages, punitive damages, costs, and attorneys’ fees. Id.

After the jury returned a verdict in favor of Graduation Solutions, Acadima moved for a judgment as a matter of law or new trial, alleging that Graduation Solutions failed to present sufficient evidence for trade dress infringement. Id. at *19. At the outset, the court observed that, to prevail on a claim of trade dress infringement based on the alleged copying of the “look and feel” of a website, a plaintiff must show (1) that its trade dress is inherently distinctive or has acquired secondary meaning; (2) that its trade dress is nonfunctional; and (3) that defendant’s product creates a likelihood of consumer confusion. Regarding distinctiveness, the court stated that “[a] mark can be inherently distinctive, or it can be descriptive and have developed a secondary meaning.” Id. (citing Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros., 529 U.S. 205, 201–16 (2000)).

Factors that are relevant in determining secondary meaning include (1) advertising expenditures; (2) consumer studies linking the mark to a source; (3) unsolicited media coverage of the product; (4) sales success; (5) attempts to plagiarize the mark; and (6) length and exclusivity of the mark’s use.

Id.

Applying each of these factors to the facts, the court determined that Graduation Solutions presented ample evidence to establish the distinctiveness and confusion elements, including proof of time and money spent developing Graduation Solutions’s website; testimony of purchasers from the copied graduation apparel sites calling Graduation Solutions’s customer service; and proof of identical color schemes and promotional text between the two websites. Id. at 20. Regarding the functionality element, the court stated that “[f]or websites, font choice, text color, background color, color and pattern of wallpaper, model poses, and arrangement of functional elements may be non-functional.” Id. In light of the testimony about the nonfunctional aspects copied from Graduation Solutions’s website, including the brand colors, redesign of the logo, and the user experience, the court found that Graduation Solutions had satisfied the functionality element. Id. at *21. Further, the court added that functional elements may be protectable as trade dress in the aggregate as part of the user experience. Id. Thus, the court ultimately concluded that Graduation Solutions presented sufficient evidence to support its trade dress infringement claim against Acadima for website copying. Id. at *21.

Using the principles applied in Graduation Solutions, this article summarizes each of the elements of a claim for trade dress infringement applied to the protection of websites from copying.

- Articulating the Elements of the Alleged Trade Dress

In order to bring a trade dress infringement claim for website copying, the plaintiff must first articulate the elements of the website that actually constitute protectable trade dress. In other words, trade dress claimants must identify the specific aspects of their website that were copied, rather than relying on general or vague assertions. Moreover, these specific elements of the website must be particular to the claimant, which is often determined by continuous use of those elements on the website over a period of time. Specificity and finality are both critical to the success of a trade dress infringement claim premised on website copying.

In Sleep Science Partners v. Lieberman, Plaintiff Sleep Science made a mandibular repositioning (e.g., snore-reducing) device and sold it on its website. No. 09-04200 CW, 2010 WL 1881770 (N.D. Cal. May 10, 2010). Sleep Science showed its product and website to Avery Lieberman. Lieberman then showed the product and website to two other individuals, who allegedly copied the website and launched a similar one under the corporate name Sleeping Well.

Sleep Science alleged that the Sleeping Well website “has the same format, design and feel as [its] website.” Id. at *2. It alleged trade dress infringement, and described its trade dress as the “unique look and feel of SSP’s website, including its user interface, telephone ordering system and television commercial.” Id. at *6. Sleeping Well defended in part on the grounds that plaintiff’s description was too vague to provide sufficient notice of the trade dress claim. Id. The court ultimately agreed with Sleeping Well. “Although it has catalogued several components of its website, Plaintiff has not clearly articulated which of them constitute its purported trade dress,” the court observed. Id. at *3.

It is essential, therefore, that plaintiff articulate the specific elements, design, combination of colors, and the like that constitute its trade dress. Vague assertions about trade dress or design elements that are common to many websites will not suffice.

- Proving Distinctive Trade Dress

A plaintiff must also show that the alleged trade dress is distinctive and non-functional, and that there is a likelihood of consumer confusion between its alleged trade dress and that of the defendant. 15 U.S.C. §§ 1125(a)(3).

Of these requirements, distinctiveness is the most difficult to establish in the context of websites. As the Supreme Court has noted, “Nothing in § 43(a) explicitly requires a producer to show that its trade dress is distinctive, but courts have universally imposed that requirement, since without distinctiveness the trade dress would not ‘cause confusion . . . as to the origin, sponsorship, or approval of [the] goods,’ as the section requires.” Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros., 529 U.S. 205, 210 (2000).

Two legal standards of distinctiveness in trade dress law have evolved in case law. In Wal-Mart, the Supreme Court ruled that the distinctiveness of product design is measured differently from that of product packaging. Product packaging refers to the appearance of the package a product comes in, as well as to interior design schemes found in stores, restaurants and hotels. Id. at 212–13. In order to be eligible for trade dress protection, the product packaging must meet the “inherently distinctive” standard, set in the Court’s 1992 ruling in Two Pesos, Inc. v. Taco Cabana Inc. 505 U.S. 763, 768 (1992). “Inherently distinctive” trade dress suggests a particular source to consumers without need for repeated association. Id. at 768.

Product design, in contrast, refers to the way a product looks and feels. Product design can only be distinctive enough to warrant trade dress protection if it has acquired “secondary meaning.” Wal-Mart Stores, 529 U.S. at 215. Secondary meaning refers to a level of distinctiveness acquired by longstanding use in the market, as opposed to the inherent design of the site. Id. at 211. In part because it must evolve over time, secondary meaning is intrinsically more difficult to demonstrate than inherent distinctiveness.

It is not clear whether, to merit protection as trade dress, the look and feel of a website must be inherently distinctive or whether secondary meaning may be shown. One argument posits that because websites are more akin to storefronts than to tangible products, the inherent distinctiveness standard of Two Pesos is more appropriate. On the other hand, that standard may be hard to apply to website design in practice. In a commercial world where many different websites may have similar general layouts, as dictated by principles of efficient user experience, what should qualify as “inherently distinctive”?

The few published decisions applying trade dress law to website copying suggest that the owners must demonstrate secondary meaning to state a trade dress claim, although few if any published decisions address whether such standard logically applies to websites in particular. See, e.g., SG Servs. Inc. v. God’s Girls Inc., No. CV 06-989 AHM, 2007 WL 2315437, at *9 (C.D. Cal. May 9, 2007).

- Secondary Meaning in the Website Context

Courts consider several factors in order to determine whether secondary meaning exists, including:

- Whether consumers in the relevant market associate the trade dress with the maker;

- The degree and manner of advertising under the claimed trade dress;

- The length and manner of use of the claimed trade dress;

- Whether the use of the claimed trade dress has been exclusive;

- Evidence of sales, advertising, and promotional activities;

- Unsolicited media coverage of the product; and

- Attempts to plagiarize the trade dress.

First Brands Corp. v. Fred Meyer, Inc., 809 F.2d 1378, 1383 (9th Cir. 1987).

In Wal-Mart, the Supreme Court noted that it was entirely reasonable to require proof of secondary meaning in order to secure trade dress protection. Wal-Mart Stores, 529 U.S. at 214. The Court reasoned that any inherently distinctive design could be protected as well by copyright or by a design patent. The implication seems to be that manufacturers could seek relief from infringement of their allegedly proprietary product designs by resorting to copyright or patent law instead of or in addition to trade dress law. Unfortunately for website owners, copyright does not protect web sites fully or entirely effectively. It is also unlikely that a website would qualify for a design patent because it is not an “ornamental design for an article of manufacture” as 35 U.S.C. § 171 requires.

The relevance of secondary meaning in the website context can reasonably be questioned. One factor traditionally used to demonstrate secondary meaning is length of time the product design has been used in the market. Length of time in the modern marketplace, however, is not an efficient proxy for consumer identification. On the Internet, companies that are relatively new, and thus have only had operational web sites only for a short time, can often develop stronger consumer associations than more established companies with less striking or resonant websites.

- The Difficulty of Proving Non-Functionality

It is well-settled that protectable trade dress cannot be functional. The Ninth Circuit Court described the functionality test as follows:

A product feature is functional if it is essential to the product’s use or if it affects the cost and quality of the product . . . . “Functional features of a product are features which ‘constitute the actual benefit that the consumer wishes to purchase, as distinguished from an assurance that a particular entity made, sponsored or endorsed a product.”

Rachel v. Banana Republic Inc., 831 F.2d 1503, 1506 (9th Cir. 1987) (citation omitted).

This raises a difficult set of issues for website protection. Every company wants its website to be functional, in that it encourages consumer use, but the overlap between website functionality and the “benefit the consumer wishes to purchase” can vary greatly. While some websites merely describe the product the customer wishes to purchase, other websites, such as search engines, review sites or booking sites, are the product the customer wishes to purchase. Accordingly, it is impossible to impose a single trade dress standard for all website look and feel cases with regard to their functionality.

Courts have approached the non-functionality requirement in website cases in different ways. At least one court has denied trade dress protection for a website based on its functionality. In an unpublished 2008 opinion, the District Court of New Jersey analyzed whether visuals illustrating various features of the bond market on the plaintiff’s website were protectable under copyright or trade dress. Mortgage Mkt. Guide, LLC v. Freedman Report, LLC, 2008 WL 2991570, at *1 (D. N.J. July 28, 2008). Because the visuals were inextricably linked to their function, the district court held that they could not meet the non-functionality requirement of trade dress. It found, however, that these functional features were entitled to copyright protection because of their creativity and “unique expression.” The decision did not extend copyright protection, however, to the look and feel of the website as a whole.

Non-functionality is somewhat easier to assess in the context of a website promoting a physical product. In Card Tech International v. Provenzano, for example, the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California concluded that both the website for a cleaning card, which is used to clean the slots of credit card machines and other card readers, and the packaging of the card were nonfunctional and qualified as trade dress. Card Tech Int’l, LLLP v. Provenzano, 2012 WL 2135357 (C.D. Cal. June 7, 2012). “There is nothing about the layout or overall appearance of the trade dress, both packaging and website, that enables the package or website, respectively, to function…. The content of the website can be arranged differently; the package can have a different appearance. Neither the appearance of the packaging nor the website provides a benefit apart from identifying the source of the product.” Id. at *6. The court concluded on this basis that protecting the website as trade dress would not “impair competition in the industry.” Id.

That said, courts have allowed trade dress claims to go forward where the copied website provided a service as well. In Conference Archives v. Sound Images, an unpublished case from the Western District of Pennsylvania, a competitor admitted to copying a product that “displays recorded video within a web browser.” 2010 WL 1626072, at *1 (W.D. Pa. Mar. 31, 2010). The court ruled that the presence of some functional features in the website does not exclude the possibility of trade dress protection. The determination of functionality, the court held, should properly focus on the “look and feel” of the website overall than on the function of its individual elements. As the court noted, look and feel can serve “several possible functions,” only some of which might bar trade dress protection, including branding, by helping to identify a set of products from one company, as well as ease of use, because users will become familiar with how one product functions (looks, reads, etc.) and can translate their experience to other products with the same look and feel. The court concluded that “the mere presence of functional elements does not by necessity preclude trade dress protection. Rather, a web site may be protectable ‘as trade dress if the site as a whole identifies its owner as the creator or product source.’” Id. at *58–59 (citations omitted).

The court’s observation that the look and feel of a website must be “distinctive, but non-functional” serves as a guide for other courts assessing the potential for trade dress protection.

- Likelihood of Confusion in Look and Feel Cases

The last requirement for trade dress infringement is proof of likelihood of consumer confusion. While the specific factors vary among the circuit courts, the Ninth Circuit’s eight-factor test to assess this likelihood is commonly applied:

- The similarity of the two trade dresses;

- The relatedness of the two companies’ products or services;

- The advertising or marketing channels each party uses;

- The strength or distinctiveness of the plaintiff’s trade dress;

- The defendant’s intent in selecting the mark, including evidence of intent to infringe;

- Evidence of actual confusion;

- The likelihood of expansion in product lines leading to more direct competition down the line; and

- The degree of care that consumers are likely to use.

AMF Inc. v. Sleekcraft Boats, 599 F.2d 341, 349 (9th Cir. 1979).

Likelihood of confusion plays an important role in website look and feel cases. In Faegre & Benson LLP v. Purdy, the plaintiff law firm sued a group that had copied its website, alleging trade dress infringement. 367 F. Supp. 2d 1238, 1240 (D. Minn. 2005). Although the defendant had labeled every page of its website as a “parody,” the plaintiff alleged that the defendant’s website “feature[d] the same color scheme, layout, buttons, fonts and graphics” as its own. Id. at 1244. The court concluded that the “overall dissimilarity” between the two sites, however, created a “low likelihood of confusion,” and the parody disclaimer further reduced that likelihood. Id. at 1245.

In contrast, consider again Graduation Solutions, where Acadima copied elements Graduation Solution’s website to sell graduation apparel and accessories. There, Graduation Solutions’s customer support department received phone calls from purchasers concerning orders from Acadima’s copycat website. 2020 WL 1466204, at *19. The court found that these misplaced calls constituted evidence of actual consumer confusion, which weighed substantially in favor of a finding of a likelihood of confusion. Id.

In sum, website copying can obviously be harmful to both the public and website owners, especially given the ubiquity of website-based commerce in the modern economy. While it is clear that trade dress claims may not be, in all instances, perfectly suited to protect the look and feel of websites, it is often the most logical and viable basis through which to protect websites from copying by competitors.

False Advertising and Unfair Competition Under Claims under Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act – a Primer

Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act provides grounds for several claims broadly categorized as “unfair competition.” 15 U.S.C. § 1125. Such claims include infringement of unregistered trademarks, false advertising, false designation of origin, and false endorsement (sometimes characterized as the misappropriation of the right of publicity). Section 43(a) claims are notoriously fact-specific and courts often weigh the equities of the case, which sometimes results in different conclusions on seemingly similar fact patterns. When pursuing a claim under Section 43(a), it is therefore essential to be familiar with particular standards applied by courts in the applicable Circuit and to find, if possible, cases with the most analogous fact patterns in that Circuit.

Generally, a claim under Section 43(a) may be maintained by any person who believes that he or she is likely to be damaged by a violation of the statute (15 U.S.C. § 1125(a)). However, Section 45 narrows the scope of this broad language, providing that the Lanham Act is intended “to protect persons engaged in [interstate] commerce against unfair competition” (15 U.S.C. § 1127). Courts have thus construed these provisions to limit protection to persons engaged in interstate commerce whose competitive or commercial interests have been harmed by the defendant’s conduct, and to hold that individual consumers do not have standing to assert Section 43(a) claims. See Made in the USA Found. v. Phillips Foods, Inc., 365 F.3d 278, 280-81 (4th Cir. 2004); Barrus v. Sylvania, 55 F.3d 468, 470 (9th Cir. 1995). Consumers are not entirely without recourse, though, and may pursue claims under applicable state consumer protection laws and file complaints with the FTC.

Importantly, Section 43(a) has two subparts aimed at different conduct and providing different types of relief. Section 43(a)(1)(A) seeks to prevent deceptive conduct that causes consumer confusion, and is the basis for claims for unregistered trademark infringement, false designation of origin, and false endorsements. Section 43(a)(1)(B) is intended to prevent deceptive commercial advertising. 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a)(1)(B), which is the focus of this overview.

False Advertising Generally

Section 43(a)(1)(B) allows plaintiffs who are commercially injured by a defendant’s false or misleading representations in commercial advertising to pursue a claim. Specifically, the prohibitions of Section 43(a)(1)(B) apply to “any commercial advertising or promotion” that “misrepresents the nature, characteristics, qualities, or geographic origin of any goods, services or commercial activities. 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a)(1)(B). The subject representation can be any statement, term, symbol, or device that conveys a false or misleading message to consumers. Such claims often involve a false statement regarding the quality, functionality or test results pertaining to the plaintiff’s or the defendant’s product, slogans that imply that a defendant’s product has a quality or function that it does not have, product names that falsely suggest a particular trait, quality or geographic origin, or audio-visual images that misrepresent a product’s performance or function.

Plaintiffs in false advertising cases often plead other claims as well, including unfair competition and deceptive trade practices under state law and common law commercial disparagement or trade libel.

Standing to sue is frequently an issue in false advertising claims. In addition to Article III standing, a plaintiff seeking to assert a false advertising claim under Section 43(a) must show that (1) the claimed injury is within the zone of interests protected by the Lanham Act, meaning an injury to a commercial interest in reputation or sales, and (2) the defendant’s deceptive advertising proximately caused the plaintiff’s economic or reputational injury, meaning the injury flows directly from the defendant’s conduct. Lexmark, 572 U.S. at 129-34. Importantly, however, the parties do not need to be competitors for standing to exist. Id. at 136.

Elements of a Claim

Broadly speaking the Lanham Act provides a false advertising cause of action against any defendant who uses a false or misleading word, symbol, description, or device in a commercial advertisement to misrepresent the nature, characteristics, or qualities of any person’s goods or services, courts (15 U.S.C. § 1125(a)(1)(B)). However, courts construing Section 43(a)(1)(B) have required the plaintiff to demonstrate additional elements, including consumer deception and materiality, to prevail. These additional elements generally include, depending on the Circuit, that (1) defendant made a false or misleading statement of fact in a commercial advertisement, (2) the statement deceived or had the capacity to deceive a substantial segment of potential consumers, (3) the deception is “material” and likely to influence a consumer’s purchasing decision, (4) the statement is made in interstate commerce, and (5) the statement injured or is likely to injure the plaintiff. See, e.g., Compulife Software Inc. v. Newman, 959 F.3d 1288, 1316 (11th Cir. 2020); Skydive Ariz., Inc. v. Quattrocchi, 673 F.3d 1105, 1110 (9th Cir. 2012); Highmark, Inc. v. UPMC Health Plan, Inc., 276 F.3d 160, 171 (3rd Cir. 2001); Pizza Hut, Inc. v. Papa John’s Int’l, Inc., 227 F.3d 489, 495 (5th Cir. 2000).

Most false advertising disputes focus on the falsity of the challenged advertisement and the extent to which it materially deceives consumers. As noted above, however, there are differences among Circuits in which specific elements are required and how they are applied. It is therefore essential that the applicable standard in the applicable Circuit be specifically identified.

Commercial Advertisements

A false or misleading statement must appear in a commercial advertisement to be actionable under Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act. 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a). In many cases, the challenged advertisement clearly is commercial (for example, a TV or radio ad). However, the parties may dispute this element in cases where the challenged statement is made outside of traditional commercial media. For these purposes, “commercial advertisements” include more than traditional widespread advertising campaigns; instead, any challenged statement may constitute a commercial advertisement if it qualifies as commercial speech that is intended to influence consumer’s buying decisions regarding the defendant’s products or services, and is disseminated widely enough to reach the relevant purchasing public. See, e.g., Grubbs v. Sheakley Group, Inc., 807 F.3d 785, 801 (6th Cir. 2015).

The level of dissemination required depends on what is typical in the relevant industry and market. Grubbs, 807 F.3d at 800-01. Defendants often argue that the challenged statement does not qualify as a commercial advertisement when it is sent to only a small number of customers. Courts have held that a statement made to targeted customers in a small industry or even a single customer when the potential number of customers is limited can satisfy the dissemination requirement. See Glob. Tubing LLC v. Tenaris Coiled Tubes LLC, 2018 WL 3496739, at *5 (S.D. Tex. July 20, 2018); Coastal Abstract Serv., Inc. v. First Am. Title Ins. Co., 173 F.3d 725, 735 (9th Cir. 1999).

False or Misleading

Two types of commercial advertisements can provide grounds for a false adverting claim under Section 43(a) – claims that are “literally” false and advertisements that are misleading because of a false implication that they convey. Plaintiffs generally seek to prove that an advertisement is literally false because this gives rise to a presumption of consumer deception, leaving little more to prove to prevail on the claim. Even when a plaintiff alleges literal falsity, plaintiffs often plead in the alternative that the challenged advertisement is impliedly false and misleading, which requires proof that the challenged statement actually deceives consumers.

Determining the Message Conveyed

Determining the message conveyed by the challenged advertisement is often the most important first step in a false advertising analysis. While the challenged advertisement’s meaning is often explicit, in many cases, a plaintiff must argue that, while not explicit, the ad implies a specific message that consumers recognize and understand even if not explicitly stated. The court then must determine whether the challenged advertisement delivers the alleged message by necessary implication before assessing the truth or falsity of the message. Clorox Co. P.R. v. Proctor & Gamble Commercial Co., 228 F.3d 24, 34-35 (1st Cir. 2000). In determining the message, courts often look to industry standards, as well as the full context of the message (including all text, graphics and surrounding content).

Literal Falsity

Courts presume that literally false advertisements are deceptive, such that the plaintiff need not to show how consumers perceive the message. See, e.g., Louisiana-Pac. Corp. v. James Hardie Bldg. Prod., Inc., 928 F.3d 514, 517 (6th Cir. 2019); Time Warner Cable, Inc. v. DIRECTV, Inc., 497 F.3d 144, 153 (2d Cir. 2007). As one might expect, however, proof of literal falsity carries a substantial burden. In general, an advertisement is “literally” false only if it is reasonably interpreted as a statement of objective fact, its claims are specific and measurable, and it is capable of being proven false. Statements that can reasonably be interpreted in different ways, or is implied or merely suggestive in such a way that a consumer must draw an ultimate conclusion are not literally false. If the challenged ad states that the defendant’s product is superior to other products without reference to concrete data, tests or studies, the plaintiff must prove that the statement is false by affirmatively showing that the defendant’s product is not superior to other products.

Misleading Advertisements

If an advertisement is not literally false, a plaintiff can still prevail by proving that the ad actually deceives consumers or, as many courts phrase it, has a “tendency to deceive” a substantial portion of its intended audience. See, e.g., Am. Council v. Am. Bd. of Podiatric Surgery, Inc., 185 F.3d 606, 616 (6th Cir. 1999)).

Puffery

Statements may be literally false or unsupported by evidence, but nevertheless not actionable as “puffery” if they merely contain generalized boasting about the qualities or characteristics of a product or service. Such puffery includes statements that no reasonable buyer would view as statements of objectively true fact, including general claims of superiority that are generally understood as opinion, see Pizza Hut, 227 F.3d at 491, or claims that are grossly exaggerated or humorous that no reasonable buyer would believe. Stokely-Van Camp, Inc., v. Coca-Cola Co., 646 F. Supp. 2d 510, 529-30 (S.D.N.Y. 2009). The difference between puffery and actionable statements or claims is often difficult determine. Specific statements touting particular qualities or superiority that is capable of being verified through testing or other data do not qualify as puffery.

Consumer Deception

Courts require plaintiffs to demonstrate that the challenged ad deceives consumers in order to prevail. There are differences from Circuit to Circuit about whether a plaintiff must prove actual deception or merely that the ad is likely to (or has a “tendency” to deceive consumers. See Pizza Hut, 227 F.3d at 497. Proof of deception therefore often requires survey evidence or other evidence of actual deception.

Materiality

In addition to the above, a plaintiff must also show that the defendant’s false or misleading statement is material, in that it affects or is likely to affect consumer purchasing decisions. Johnson & Johnson Vision Care, Inc. v. 1-800 Contacts Inc., 299 F.3d 1242, 1250-51 (11th Cir. 2002). Many courts equate a “material” misrepresentation with one that concerns an inherent quality or characteristic of a good or service. Nat’l Basketball Ass’n v. Motorola, Inc., 105 F.3d 841, 855 (2d Cir. 1997)). Factors bearing on the materiality of a challenged statement include the importance to consumers of the product or service feature referenced in the statement and the degree of falsity of the statement. Pom Wonderful LLC v. Welch Foods, Inc., 737 F. Supp. 2d 1105, 1113 (C.D. Cal. 2010). Again, proof of materiality may require survey evidence demonstrating that consumers considered the challenged statement important to buying decisions, proof that the misrepresentation actually caused consumer(s) to purchase the subject products or services, and/or a finding that materiality is “self-evident” from the context. Some but not all courts presume materiality in the presence of proof of actual falsity. See Pizza Hut, 227 F.3d at 497.

Remedies

The Lanham Act allows for both injunctive relief and monetary damages for false advertising. 15 U.S.C. § 1116. The principles that govern monetary relief under the Lanham Act generally (including trademark infringement claims) also govern monetary relief for false advertising under Section 43(a)(1)(B).

Courts typically do not require proof of actual consumer deception for injunctive relief. A plaintiff need only show that the defendant’s false or misleading advertisement has a tendency to confuse consumers by showing that the advertisement misled at least some consumers. Pizza Hut, 227 F.3d at 497-98. Injunctions in false advertising cases generally prohibit similar misrepresentations in the future, and in some cases require the defendant to take affirmative steps to correct misrepresentations through corrective advertising. See Energy Four, Inc. v. Dornier Med. Sys., Inc., 765 F. Supp. 724, 735 (N.D. Ga. 1991).

To recover monetary damages, a plaintiff must show both actual consumer deception resulting from the false or misleading advertisement, and that the defendant caused actual harm to the plaintiff’s reputation or sales. Some Circuits, including the Ninth Circuit in particular, do not require proof of actual injury to justify damages. Instead, courts are permitted in their discretion to award monetary damages based on a totality of the circumstances. Southland, 108 F.3d at 1146. Intentional deceptive advertising may give rise to a rebuttable presumption of compensable injury, Porous Media Corp. v. Pall Corp., 110 F.3d 1329, 1336-37 (8th Cir. 1987); U-Haul Int’l, Inc. v. Jartran, Inc., 793 F.2d 1034, 1040-41 (9th Cir. 1986), as does proof of literal falsity. Pizza Hut, 227 F.3d at 497. Courts may also award damages in the amount spent by plaintiff on advertising to respond to the defendant’s false claims. Balance Dynamics Corp. v. Schmitt Indus., Inc., 204 F.3d 683, 692-93 (6th Cir. 2000).

Cease and Desist Letters – What can go wrong?

So, your client comes to you and says: Somebody is infringing our trademark or our patent – crush them. I am sure we have all seen cease and desist letters drafted by a lawyer who is trying to follow the client’s instructions to “crush them.” Those letters will:

Demand an immediate halt to all business operations involving the alleged infringement;

Demand immediate destruction of the allegedly infringing items;

Demand identification of all customers who purchased the infringing items;

Demand an accounting of all profits earned as a result of the infringement;

Demand compensation, including surrender of the infringer’s first-born child.

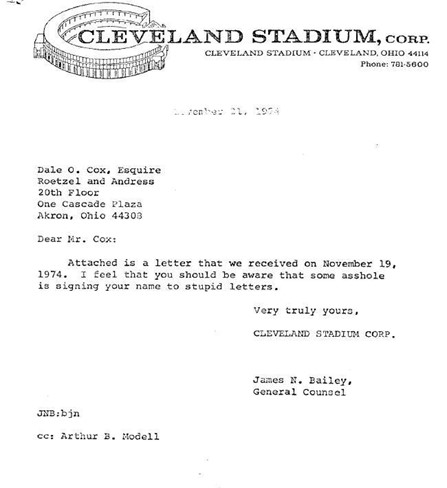

Sometimes those letters work, but not usually. Sometimes, you get a response like this:

Our fact pattern shows some of the things that can go wrong with a poorly conceived cease and desist letter. It can blow up in your face if you have not done your research about who actually owns the IP rights at issue. For example, in Protech Diamond Tools, Inc. v. Liao, 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 53382, *23 (N.D. Cal. 2009), the plaintiff sent a cease-and-desist letter demanding that the defendant stop using the plaintiff’s federally registered mark. When the defendant refused, the plaintiff filed suit seeking a preliminary injunction. Although the plaintiff’s mark was incontestable, the defendant was able to demonstrate that the defendant had been using the mark prior to plaintiff’s registration and, therefore, owned common law rights to the mark. The court refused to enter a preliminary injunction and also refused to dismiss the defendant’s counterclaim to cancel the plaintiff’s registration for the mark.

A poorly conceived cease-and-desist letter can also create adverse publicity. For example, in 2017, a craft brewer known as BrewDog, was about to launch a line of vodka and gin with the trademark “Lone Wolf.” Shortly before the launch, BrewDog learned that a small pub had just started using the name Lone Wolf, so BrewDog’s lawyers sent a cease-and-desist letter. The pub decided to rebrand itself as just “The Wolf,” but went on social media to explain why. media. That prompted a firestorm of negative publicity for BrewDog such as:

@TheWolfBham this is really disappointing @BrewDog. Not cool at all. This Equity Punk won’t condone corporate bullying. #WhoNeedsPunk

@BrewDog you should be ashamed for bullying this superb independent business. Shame on you!

this is a simple demonstration that @BrewDog are just another multinational corporate machine. Not independent ‘punk’ movement.

BrewDog eventually responded as follows:

It appears our lawyers did what lawyers do and got a bit carried away with themselves, asking the owners of the new ‘Lone Wolf’ bar to change its name, as we own the trademark. Now we’re aware of the issue, we’ve set the lawyers straight and asked them to sit on the naughty step to think about what they’ve done.” The legal team is sorry for their actions and that they have been put on “washing up duty for a week.”

I doubt that the lawyers sent the cease-and-desist letter without the client having asked them to do so and blaming the lawyers probably did not do much to mitigate the adverse publicity.

A poorly conceived cease-and-desist letter can have other adverse consequences. For example, it is a factor that can be considered in determining whether you are subject to personal jurisdiction in an unfriendly forum. “A cease and desist letter is not in and of itself sufficient to establish personal jurisdiction over the sender of the letter.” Yahoo! Inc. v. La Ligue Contre Le Racisme Et L’Antisemitisme, 433 F.3d 1199, 1208 (9th Cir. 2006); J.M. Smucker Co. v. Hormel Food Corp., 526 F. Supp. 3d 294, 303 (N.D. Ohio 2021). In Smucker, the Court explained:

The mere sending of cease and desist letters is insufficient to give rise to personal jurisdiction. HealthSpot, Inc. v. Computerized Screening, Inc., 66 F. Supp. 3d 962, 969 (N.D. Ohio 2014) (citing Red Wing Shoe Co. v. Hockerson—Halberstadt, Inc., 148 F.3d 1355, 1360-61 (Fed. Cir. 1998)). This is so because even though cease-and-desist letters alone are substantially related to declaratory judgment claims, such minimum contacts are not sufficient to satisfy the concepts of fair play and substantial justice necessary to render the exercise of personal jurisdiction over a non-resident defendant reasonable. The owner of intellectual property rights “should not subject itself to personal jurisdiction in a forum solely by informing a party who happens to be located there of suspected infringement. Grounding personal jurisdiction on such contacts alone would not comport with principles of fairness.” Red Wing Shoe, 148 F.3d at 1360-61 (citing Asahi Metal Indus. Co. v. Superior Ct. of Cal., 480 U.S. 102, 121-22, 107 S. Ct. 1026, 94 L. Ed. 2d 92 (1987) (Stevens, J., concurring in judgment)).

Id. As the Ninth Circuit and other circuits have explained, “[t]here are strong policy reasons to encourage cease and desist letters.” Yahoo!, supra, 433 F.3d at 1208. If doing so subjected a sender to jurisdiction in the alleged infringer’s state, the sender would be incentivized to file suit in its home state rather than attempting to resolve the dispute outside of litigation. Id. Nevertheless, “[i]n conjunction with other contacts . . . a cease and desist letter can form the basis for specific jurisdiction.” Attilio Giusti Leombruni S.p.A. v. Lsil & Co., Inc., 2015 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 189569, *21-22 (C.D. CA 2015).

A poorly conceived cease-and-desist letter may give the infringing party the opportunity to file a declaratory judgment action against you in a jurisdiction that you may find to be unfavorable. In MedImmune v. Genentech, 549 U.S. 118, 127 (2007), the Supreme Court broadened the scope of declaratory judgment jurisdiction. It ruled that a party can seek a declaratory judgment when there is “a substantial controversy, between parties having adverse legal interests, of sufficient immediacy and reality to warrant relief.” Id. at 127 (quoting and citing Maryland Cas. Co. v. Pac. Coal & Oil Co., 312 U.S. 270, 273 (1941)).

Although courts should look at the totality of the circumstances in deciding whether declaratory relief is warranted, the contents of a cease-and-desist letter can be a key factor. A strongly worded cease and desist letter, with a direct accusation of infringement, will likely be sufficient to meet the MediImmune test.

What can you do to avoid creating declaratory judgment jurisdiction? The Federal Circuit has ruled that “a communication from a patent owner to another party, merely identifying its patent and the other party’s product line” is not enough for a definite and concrete dispute. Hewlett-Packard Co. v. Acceleron LLC, 587 F.3d 1358, 1362 (Fed. Cir. 2009). The problem with this approach is that a cease-and-desist letter that seeks to avoid creating declaratory judgment jurisdiction may not be sufficient to put the infringer on notice for purposes of damages. According to the Federal Circuit, “the actual notice requirement of § 287(a) is satisfied when the recipient is informed of the identity of the patent and the activity that is believed to be an infringement, accompanied by a proposal to abate the infringement, whether by license or otherwise.” SRI Int’l, Inc. v. Advanced Tech. Labs., Inc., 127 F.3d 1462, 1470 (Fed. Cir. 1997). Although the SRI opinion states that the tests for declaratory judgment jurisdiction and for Section 287 notice do not conflict, SRI was decided before MediImmune. I have not found any post-MediImmune cases that have harmonized these apparently conflicting positions.

Another risk that you face with a poorly conceived cease-and-desist letter is a claim for tortious interference. A baseless cease and desist letter can give rise to a claim for tortious interference. See, e.g., Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., 797 F.2d 70, 75 (2d Cir. 1986). In that case, Nintendo counterclaimed for tortious interference because Universal had sent cease-and-desist letters to Nintendo’s licensees asserting that Universal owned the “King Kong” trademark and Nintendo’s “Donkey Kong” game infringed Universal’s rights. The Second Circuit upheld the district court’s grant of summary judgment to Nintendo because of the substantial evidence of Universal’s bad faith in sending the cease-and-desist letters.

So, what conclusions should we draw.

First, have a strategy. What are you really trying to accomplish? What is the harm you are trying to stop or prevent? What is the best way to do so? From whom should the letter come? Should the client send it or should it be on a lawyer’s letterhead?

Second, once you have a strategy, make sure you have your facts straight. You would not file a lawsuit without doing due diligence. The same should be true of a cease-and-desist letter. I am not suggesting that you have to comply with Rule 11 before sending a cease-and-desist letter, but some investigation is appropriate. If you think someone is infringing your trademark, try to find out when they first started to use the mark. At a minimum, see if they have a trademark registration of their own.

Draft the letter with the assumption that it will be posted on social media. Assume that your audience is not just the suspected infringer, but also anyone with whom you are or want to do business as well as all of your employees. Your cease-and-desist letter should not be threatening – it should be persuasive. When someone reads the letter, you want them to understand why you are the victim – you do not want the reader to think that the infringer is the victim.

The letter should clear identify your rights and, as long as you are not concerned about a declaratory judgment, why your rights are being infringed. The letter should also suggest a remedy. The remedy should be reasonable. If you are asking someone to change their name or stop using an infringing mark, consider giving them a reasonable period of time to transition to a new name or mark.

If you are concerned about a declaratory judgment action, instead of alleging infringement, provide a copy of the patent or trademark registration and ask the infringer to explain why its products or services do not infringe. A variation is to send a copy of the patent or registration and ask whether they want to acquire a license. Of course, that assumes you are willing to license the patent or trademark.

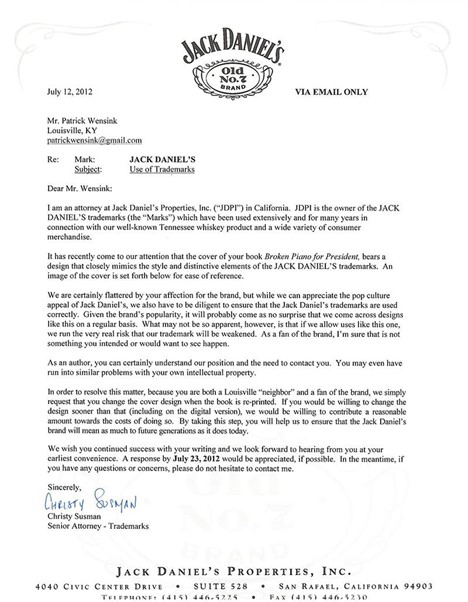

The final topic I want to mention is humor. A humorous cease and desist letter can be very effective. I have attached several examples of some well-done cease and desist letters that some people might find amusing.

I think this is a very effective cease-and-desist letter. This has a touch of humor in it, but it is also meant to be persuasive. It is not threatening – “We are flattered by your attention.” It is also explanatory – “What may not be so apparent . . . .” It co-ops the recipient – “As an author, you can certainly understand . . . .” Notice the remedy – change the cover the next time you print – a very reasonable and inexpensive remedy. Jack Daniels even offers to help pay for a change earlier than the next printing.

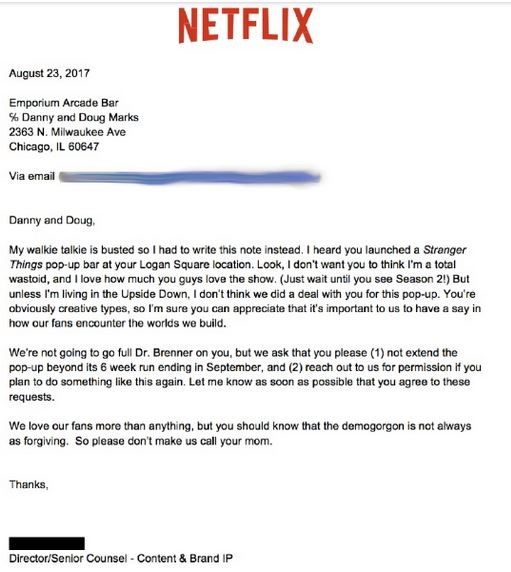

The next letter from Netflix is also pretty effective.

I am not very familiar with the Stranger Things show, but I presume that much of what is referenced in the letter is tied to the show.

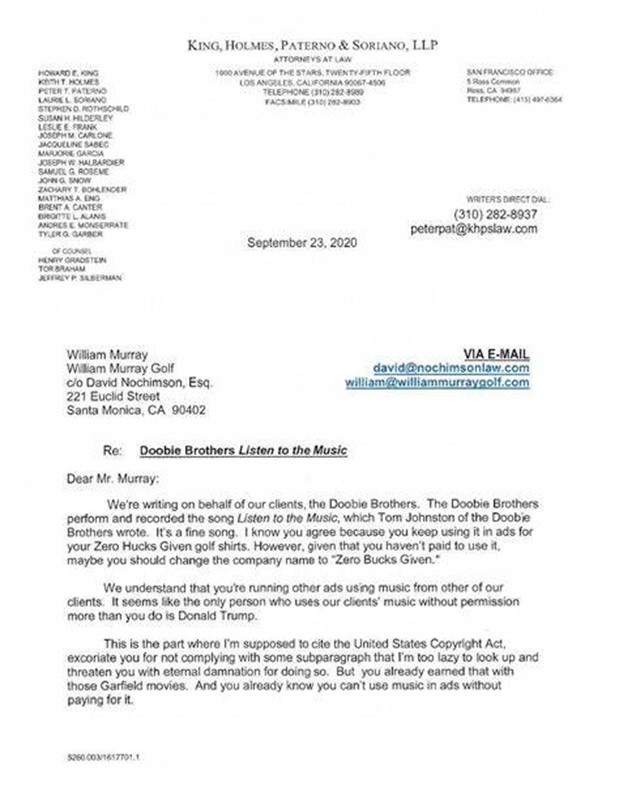

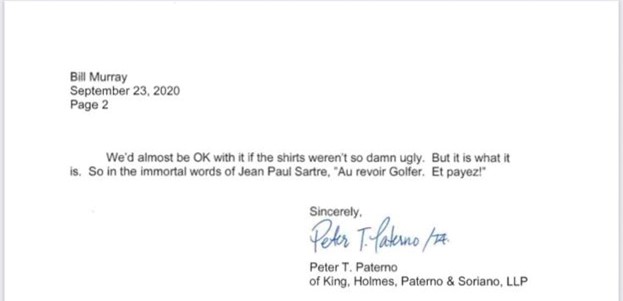

Finally, we have a letter from an attorney representing the Doobie Brothers to Bill Murray, the comedian. This letter violates most of the rules for a cease-and-desist letter, but when you learn that the attorney who wrote it is not only the lawyer for the Doobie Brothers, but also one of Bill Murray’s golfing buddies, then you can understand why it can be effective.

While humorous cease and desist letters can be effective, they are also can be risky. The recipient of the Netflix letter might not take it seriously. The letter itself can be viewed as condescending. While I think that most readers would find it humorous, not everyone might. If only you think it is funny, then you run a public relations risk.

The letter to Bill Murray illustrates my final point: Everything I have said is more of a guideline than a rule. Sometimes you just have to send a nasty letter. If you do, do it because you have considered your other options and concluded that this is your best option. And, if you do, then crush them.