The “process of Creative Destruction is the essential fact about capitalism.”

Joseph Schumpeter

Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy

Over the past decade, society, its members, and the economy have undergone what seem to be unprecedented shocks, changes, transitions, and disruptions. Brexit, the “Great Recession” triggered by the mortgage-backed securities meltdown, Covid-19, immigration, the war in Ukraine and other geopolitical unrest, supply chain interruptions, fossil fuel restrictions and price fluctuations, concerns about climate change, and other events and “crises” have led some to question where we as a civilization are, and whether the existing order and humanity can continue.[i] Calls for drastic changes and a “Great Reset” in our culture, economy, and lives are heard over the din.[ii]

Yet, those reactions and responses ignore both lessons of history and the very structure of an economy which has, to a great extent and because of its very nature, driven many of these disruptions. The reality is that the changes which society now faces are not unprecedented. Instead, history and its students offer numerous examples of drastic changes and the destruction of existing systems, structures, and methods, and guidance on how one can successfully navigate in and thrive from those changes. Given that one of the strengths of a capitalist economy is that it “is by nature a form and method of economic change and not only never is but never can be stationery,”[iii] the “gales” now facing us all are, in fact, opportunities.

Schumpeter’s Gale

Joseph Schumpeter (1883-1950) was an Austrian political economist who originally studied law in Vienna. He taught at universities in what is now Ukraine, as well as Germany and Austria. He joined the faculty of Harvard University, first as a visiting lecturer and then, after emigrating to the United States in 1932, as a professor. His writings include Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (1942), History of Economic Analysis (1954), and Business Cycles: A Theoretical, Historical and Statistical Analysis of the Capitalist Process (1939).[iv]

In his most cited work (Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy), Schumpeter coined the phrase “creative destruction” to refer to the constantly evolving nature of a capitalist economy. After rejecting theories relating to “perfect competition” and productivity, Schumpeter acknowledged Karl Marx’s observation that “in dealing with capitalism, we are dealing with an evolutionary process.” Thus, he stated:

This evolutionary character of the capitalist process is not merely due to the fact that economic life goes on in a social and natural environment that changes and by its change alters the data of economic action; this fact is important and these changes (wars, revolutions and so on) often condition industrial change, but they are not its prime movers. Nor is this evolutionary character due to a quasi-automatic increase in population and capital or to the vagaries of monetary systems of which exactly the same thing holds true. The fundamental impulse that sets and keeps the capitalist engine in motion comes from the new consumers’ goods, the new methods of production or transportation, the new markets, the new forms of industrial organization that capitalist enterprise creation creates.[v]

Thus, he continued:

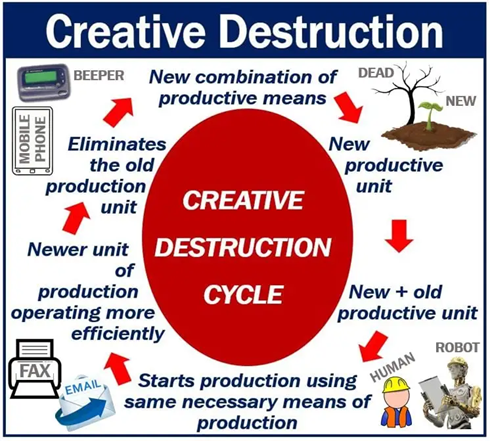

The opening up of new markets, foreign or domestic, and the organizational development from the craft shop and factory to such concerns as USS Steel illustrate the same process of industrial mutation—if I may use that biological term—that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one. This process of Creative Destruction is the essential fact about capitalism. It is what capitalism consists in and what every capitalist concern has got to live in. [vi]

As summarized by Professor Leonardo Burlamaqui of the State University of Rio De Janiero, Schumpeter’s insight was:

First, since we are dealing with a process whose every element takes considerable time . . . we must judge this performance over time. Second, since we are dealing with an organic process . . . every piece of business strategy acquires its true significance only against the background of that process and within the situation created by it. It must be seen in its role in the perennial gale of Creative Destruction. Third, from that perspective, business strategies and decisions have to be understood as an attempt to deal with the situation that is sure to change presently—as an attempt by those firms to keep on their feet, on ground that is slipping away from under them.[vii]

A critical part of Schumpeter’s analysis involved his critique of more traditional economic analyses. Typically, economists would look at the world in a static manner, evaluating the introduction of a new policy on the world in its present state. Schumpeter, on the other hand, viewed capitalism and economics as dynamic forces, with the result that the new technology or business being introduced into the economy needed to be understood not just in the manner in which it affects existing systems and structures, but more importantly, from the standpoint of future systems which themselves arise from the introduction of the new technology or business model, and how those, in turn, may lead to further innovation or destruction.[ix]

Thus, for instance, in Schumpeter’s view, it would short-sighted and erroneous to view the introduction of the horseless carriage by considering how it would affect horse breeders, coachmen, and manufacturers of buggy whips, wooden wheels, carriages, and horse harnesses. Instead, a proper analysis would take into account the changes created by this new technology, and how they, in turn, lead to further changes and innovations. Thus, one would consider the growth of motors and components needed to power and operate the vehicles, the development of chassis, the refining and delivery of fuel and oil, and, over time, such innovations as the gas stations, drive-in movies, car washes, and suburbia. Many, if not most, of these changes would have been wholly unforeseeable when the new technology or systems were introduced; thus, the struggle for those looking to thrive in the “gale of creative destruction” is to predict, anticipate, and adapt to the long-term effects of the technology changes.

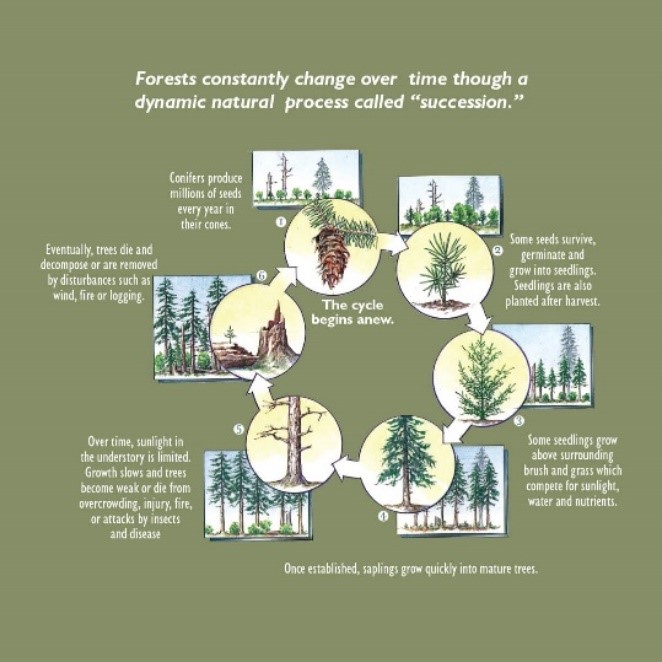

The cycle posited by Schumpeter is not dissimilar to the life cycle of a forest. From meadow or other ground which is devoid of trees (whether because of fire, decomposition, or other reasons), a young forest takes hold. This leads to habitats suitable for other plants and animals. As the forest matures, competition among the trees and other vegetation challenges the existing conifers, leading to new plants and animals. More mature forests are created by crowding out some of the earlier kinds of trees and plants; as those grow, they become more susceptible to environmental challenges, which, eventually, lead to the destruction of the forest and a restarting of the cycle.

In 1970, futurist Alvin Toffler argued, “that unless man quickly learns to control the rate of change in his personal affairs as well as in society at large, we are doomed to a massive adaptational breakdown.”[xi] Toffler discussed what he perceived to be not just ongoing changes in society and its structures, but in fact an increasing rate of change. Unless there were an acknowledgement and an addressing of what he believed was the lagging pace of human response, Toffler concluded that this path would lead to “distress, both physical and psychological, that arises from an overload of the human organisms physical adaptive systems and its decision-making processes,” something he defined as “future shock.”[xii] Consequent symptoms, he believed, would include anxiety, hostility to authority, senseless violence, physical illness, depression, apathy, and a feeling by “victims” of a need for withdrawal.[xiii]

Since Toffler wrote his seminal work (Future Shock) in 1970, changes in society, systems, businesses, technology, and geopolitics have been enormous. It is beyond the scope of this paper to address whether Toffler’s prognosis of the impact of these changes has proven true. What is undeniable, however, is that the world is no longer one in which written communications are predominantly made by letter, telegram and Telex; computers are mainframes and dumb terminals; international travel is restricted to those who could afford the high airfares of the time, manned space flight was limited to the United States’ Apollo program, telephones were sold and run by “Ma Bell,” the Internet was, for the most part, a U.S. Department of Defense project (ARPAnet), and home electronic gaming had not even been introduced through “Pong.”

Historical Examples

One can reach into history and find numerous examples in which new technology or systems destroy the existing technology and business methods. In some cases, those new systems themselves are subsequently destroyed by further competition or wither away. Still, there are also many examples where existing participants in the market recognize that paradigm shifts are coming, and then embrace (and sometimes advance) these changes in order not just to weather the storm, but in fact to thrive in it. It is also the case that some pioneers may lost sight of what their technology is and what its potential may be, and in doing so, may fall away in favor of others who have a better vision of how to exploit the changes.

A review of the Fortune 500 from 1955 reflects that as of 2019, only 52 of those companies are on the list in 2019.[xiv] A comparison of companies that have fallen from that list since 1955 – including American Motors, Brown Shoe, Collins Radio, Detroit Steel, and Zenith Electronics – with those which appear on both –Boeing, Campbell Soup, General Motors, and Procter & Gamble[xv] — does not at first blush reveal a reason for these difference in performance: both groups include auto manufacturers, consumer goods manufacturers, and technology companies. What seems apparent, however, is that those who remain vibrant have adapted to and grown from the changes in consumer demands and societal needs, and the “market disruption . . . driven by the endless pursuit of sales and profits that can only come from serving customers with low prices, high quality product and services, and great customer service.”[xvi]

The digital revolution, and more recently society’s responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, have fueled and even accelerated this process. As noted in one report,

Innovation has flourished during the pandemic, as new solutions have displaced the way we’ve done things before. As all this creative destruction makes its way through the economy, disruptive forces are especially concentrated in several sectors, where entire industries are blurring together into fast-growing “hybrid industries” – notably digital healthcare, retail-tainment, and e-mobility.[xvii]

These “hybrid industries” allow a company to apply its core strengths in order to adapt to changes in society, technology, and purchaser requirements, using existing know-how and personnel that are already part of the company and its culture. As a few examples discussed below illustrate, the ability to identify changing currents and environments, and to then use one’s expertise and core strengths to adapt, is nothing new.

A. Body by Fisher

From 1908 until 1984, the door sills of many, if not most, of General Motors’ cars bore an badge which had the image of a carriage and the words, “Body by Fisher.” Albert, Charles, and Fred Fisher were part of a family of blacksmiths and horse-drawn carriage builders from Ohio. They moved to Detroit in the early 1900s and opened “Fisher Body” in 1908.[xviii] Using their existing knowledge and experience, and recognizing that there would be different strains on the body of a “carriage” when it was part of a horseless one (as opposed to a horse-drawn one), the Fishers worked to perfect a product that would meet the needs of automobile manufacturers. Even more, they realized even before the rest of the automobile industry that car bodies which had tops and were enclosed – coincidentally, the style used in horse-drawn carriages – would optimize the ability of consumers to use these new motor-driven vehicles in all kinds of weather. They thus worked to develop and then promote that design, capitalizing on their insight.[xix]

By 1910, Fisher Body supplied all closed body frames used by Cadillac, Buick, and Oldsmobile, and also provided car bodies to Ford and Studebaker.[xx] In 1919, 60 percent of the company was purchased by General Motors.[xxi] The remaining shares were sold to General Motors in 1926, at the price of $88 million.[xxii] Until 1984m Fisher Body continued as a division within General Motors, operating 23 stamping, body-assembly and trim plants, and GM cars continued to carry the “Body by Fisher” carriage logo until the mid-1980s.

B. Apple iPhone

In 2007, Apple launched its first generation of iPhone. This device did not spring up from whole cloth: instead, its development began in 2004. At that time, Apple was mostly known for its desktop and portable personal computers and its iPod MP3 players. Of perhaps more financial significance, however, was the fact that Apple’s iTunes Music Store had become ubiquitous; selling over 100 million songs in its first 15 months, and achieving a 70% market share in legal online music download services.[xxiii] Steve Jobs recognized that with the growth of mobile phones which had more and more features, Apple’s lucrative music-player and distribution business would be threatened unless Apple got into the mobile phone business.[xxiv] After some initial efforts were discarded because of limitations in technology, Apple decided not to partner with the then-leading mobile phone company, and instead developed its own phone which could fully integrate musical functions into the smartphone. It thus released a device that combined a fully integrated mobile phone, music player, and internet access device to great fanfare in early 2007.

C. The Wright Brothers[xxv]

On December 17, 1903, bicycle manufacturers Wilbur and Orville Wright “flew into history” on a beach in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Using their experience with bicycles, as well as observation, over several years the Wright Brothers had developed a three-axis control system which gave them lift, control, and stability.[xxvi] Once those were perfected, they added power. The result was a heavier-than-air powered machine which, on that December day, made four flights, the longest being 852 feet flown over a period of 59 seconds.

Yet, despite the fact that they were, by every definition, pioneers, the Wright brothers let this advantage pass them by. Instead of capitalizing on their revolutionary aircraft and reaping the benefits of their work (which by 1905 included a craft which could circle, climb, and fly for 30 minutes) by publicizing and marketing their developments, the Wright Brothers shied away from exposing their machine to the public and even buyers because of their fears that exposure of their designs and secrets would lead to copying. This secrecy opened the door to competition, and by 1906, Alberto Santos-Dumont had achieved controlled flight – and public recognition.

The Wrights treated the accomplishments of Santos-Dumont and others with disdain, and still declined to promote their products through public displays. Instead, Wilbur focused on sales. As competition grew, the Wrights focus shifted to the courtroom, with the result that others continued to innovate while the Wrights let their designs stagnate. When eventually the Wrights were vindicated by success in their patent infringement claims (and while they did receive royalties as a result), the aircraft designers and builders whom they chose to take on through litigation had long since flown over the horizon, and in October of 1915, Orville Wright sold the business to a group of investors.

D. Sedgwick LLP[xxvii]

The law firm which became Sedgwick LLP began in 1933 in San Francisco. Over the years, it developed a well-regarded practice in insurance and product liability law, and by 2008 had 380 lawyers in offices throughout the country. In 2012, its gross revenue was $212 million. Sedgwick was known as the “insurance industry’s Rolls Royce – high cost, high performance, and a brand synonymous with trust, competence, and old-school cred.”[xxviii] The firm relied upon “seemingly endless billable hours from clients that reliably pay their bills, and do so at a rate that eclipsed the typical small-firm insurance shop.”[xxix]

Unfortunately for the billable hours model used by Sedgwick, when the financial and business world underwent tremendous disruptions beginning in 2008, insurers took stock, and started to put pressure on the firms they hired.[xxx] As this included a demand for efficiency and more competitive rates, Sedgwick’s profits-per-hour took a significant hit. As Sedgwick had not surveyed the horizon and shifted to systems which maximized efficiency, this became a case of “we lose money on every sale, but make it up on volume.” As a result, in October 2017, Sedgwick filed a Chapter 11 Bankruptcy, and closed its doors shortly thereafter.

———

What distinguishes the Fisher Brothers and the iPhone, on the one hand, from the Wright brothers and Sedgwick, on the other? Why were a family of blacksmiths and horse-drawn carriage makers and blacksmiths able to thrive (and even sell their business for over $3.8 billion in 2023 dollars) when their original market was run over by new technology, whereas the pioneers and inventors of a whole new business and service category — powered flight – languished and withered ten years after their breakthrough? Why was a technology company founded to make user-friendly small computers for homes and offices able to create a hand-held communications device which transformed not just the telephone, but also music, electronic communications, and the ability of billions to readily and instantaneously access information; whereas a well-regarded, well-positioned law firm with decades of experience and good will collapsed at a time when the underlying raw materials essential to its business – the filing of personal injury lawsuits – remained strong?

In each case, it is clear that significant changes were happening that affected the company, its area of business, and even the larger society as a whole. Some of these were initiated by the company itself, while others came from outside forces. Those entities which grew in the midst of the “gale” of change did not just hunker down in the hope that they could continue following its present path and weather the storm. Instead, they early on recognized what was happening (including possible threats to their business)[xxxi], considered how their experience and expertise might be adapted to the change, and grew stronger as a result. Thus, the Fisher brothers used their experience in designing and building carriages to develop automobile bodies and components were the foundation of General Motors cars for decades. Apple applied its expertise in user-friendly computers, small digital music devices (and a music store), internet access, and technology development to skip over the then-dominant stand-alone “personal digital assistant” devices, and applied it to jump-start the then-nascent category of “smart phones.” Both Fisher and Apple recognized the gale of destruction (automobiles wiping out the horse-drawn carriage; smart phones overtaking large computers, CD collections, and limited-capability phones), considered their expertise, adapted and created, and thrived.

In sharp contrast, the Wright brothers initially used their expertise as manufacturers of machines (bicycles) for which balance and stability were critical issues in order to help them analyze and solve the problem of developing a system for flight stabilization. By doing so, they themselves created a “gale” of destruction in the area of transportation, in which powered flight would quickly supersede older, slower means of transportation. Yet, despite the extraordinary advantages they had not just by being the first to successfully develop motorized flight, but also in perfecting their machines to the point that in 1905, they had built a “craft . . . so advanced that nobody but the small crowd of eyewitnesses that had gathered in the field could believe it,”[xxxii] the Wrights affirmatively disregarded competition, demands for publicity, and the market for less-expensive flying machines, to the point that twelve years after Orville Wright made the first controlled powered flight, he found himself separated from the business and enterprise he and his brother had created. Similarly, Sedgwick locked itself into a business model that was unsuitable for changed economic pressures and customer demands; thus, despite its experience and expertise in representing insurers, it found itself unable to survive when the gale hit. Both the Wright brothers and Sedgwick, then, relied upon the existing value of their name and a level of expertise, and in doing so, failed (or refused) to adjust and adopt their practices when the winds of destruction came through and changed what the customers required.

Thriving in the Current “Gale”

Corporations, law firms, consumers, and society as a whole is faced with wide-ranging changes and disruptions, some positive, some negative. Globalization, the increasing ubiquity of digital devices and systems, the growth and use (and abuse) of social media and its instant reach have forced many to change from a local, measured approach to a more urgent, global perspective. The pandemic (and consequent governmental responses) have led to reassessments of social interactions, population density, transportation, and how and where work is done; these shocks are still being absorbed and understood, and they will likely reverberate for many years to come. Supply chain interruptions during the past several years have had immediate and longer term impacts, and have caused many to rethink how sourcing, inventory, and business relationships should operate. The recent movement from years of “cheap money” to significantly higher interest rates affects virtually any person or business which requires funding to do business or purchase goods or materials. Fuel availability and cost, and the desire by some to move towards a transition from long-established sources of energy, has and will lead to reassessments and adjustments throughout the economy. The conflict in Ukraine reverberates throughout the globe, and tensions in other parts of the world are causing disruption and loom as even greater forces for change. Businesses – including law firms – are seeing AI being suggested as a means for efficiency (or, in some cases, as a replacement) for some of the services they offer. Human migration, changes in the climate, rapidly shifting governmental policies, and food supply concerns all contribute to a feeling of multiple “gales,” both present and in the forecast.

While it is important to be able to survive through a stressful sequence of events,[xxxiii] rather than view these events as figurative hurricanes which one hopes to weather by “battening down the hatches,” the examples of the Fishers and of Apple offer models for thriving in this environment. Firms should consider the nature of the gale(s) and how they are impacting their sector, suppliers, customers, employees, and businesses. During the storm (and preferably before), they should undertake a detailed and critical evaluation and inventory of the skills, expertise, assets, relationships, and know-how they have developed. This analysis should be done not only in the static context of the current business structure, but more critically, with an eye toward how those assets can be used to grow in what may be a dynamic and radically different environment and market, which itself may necessitate a drastic transformation of how those assets are used. Thus, rather than be a “Blockbuster Video” be a Netflix, the latter of which, after it recognized (and if anything accelerated) a radical change in the way in which consumers watched movies at home, used its expertise in remotely facilitating consumers easy access to home videos.

One current change which seems to be the result of combined “gales” blowing from the pandemic and digital developments is the growth of “hybrid industries.” These often involve businesses or systems in several sectors which had previously operated separately, and which are coupled so as to apply the core strengths of each “donor” company or sector to create what may be an entirely new way of doing business, and to thrive in the face of new market forces.[xxxiv] Examples include,

- “Retail-tainment,” where rather than offering consumers traditional retail experiences, retailers offer customers on-line options and content (such as Amazon Prime). Other examples include combining the ability to browse, shop, customize and order on-line through a sophisticated Internet experience, with customer service and delivery made available through bricks-and-mortar hands-on presences and local shopping assistants.

- Digital health, which can include streamlining the provision of some health care and testing through on-line access. This can be cost-effective and may also extend the availability of testing and specialized care to communities which had traditionally been ill-served.[xxxv]

For law firms, the lesson of Sedgwick is not just that “’the billable hour is the culprit of everything.’”[xxxvi] Firms which hope to avoid its fate should not rely merely upon their long-standing reputations and expertise, a deep bench of associates, and the ability to capture billable hours. Instead, to thrive the need to stay on top of changes in the profession and client needs, evaluate and (where appropriate) adopt new technologies or methods, and constantly adapt how they do business and how they work with their clients.[xxxvii]

[i] See generally, A. Loeb, “How Much Time Does Humanity Have Left?”, Scientific American, May 2021, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-much-time-does-humanity-have-left/

[ii] “The Great Reset,” World Economic Forum, https://www.weforum.org/great-reset

[iii] J. Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy..

[iv] https://www.brittanica.com/biography/A. Joseph-Schumpeter.

[v] Schumpeter, supa.

[vi] Id.

[vii] L. Burlamaqui “Schumpeter’s Creative Destruction as a radical departure: A New Paradigm for Analyzing Capitalism.” Centro Barasileiro derelacoes Internacionas, Núcleo Economio Politica, March 2022. https://cebri.org/media/documentos/arquivos/Leonardo_Burlamaqui_-_Schumpet622927e254f92.pdf.

[viii] From Market Business News Glossary, https://marketbusinessnews.com/financial-glossary/creative-destruction/

[ix] Generally, see D. Adler, “Schumpeter’s Theory of Creative Destruction,” Carnegie Mellon University Department of Engineering and Public Policy. https://www.cmu.edu/epp/irle/irle-blog-pages/schumpeters-theory-of-creative-destruction.html

[x] https://www.idahoforests.org/content-item/tree-forest-life-cycle/

[xi] A. Toffler Future Shock, p. 11 (1970).

[xii] Id., p. 556.

[xiii] Id.

[xiv] M. Perry, “Only 52 US companies have been on the Fortune 500 since 1955 thanks to the creative destruction that fuels economic prosperity.” American Enterprises Institute, March 22, 2019 A.E. Ideas, https://www.aei.org/carpe-diem/only-52-us-companies-have-been-on-the-fortune-500-since-1955-thanks-to-the-creative-destruction-that-fuels-economic-prosperity/.

[xv] Id.

[xvi] Id.

[xvii] S.P. Viguerie, N. Calder, B. Hindo, “2021 Corporate Longevity Forecast,” Innosight, May 2021, https://www.innosight.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Innosight_2021-Corporate-Longevity-Forecast.pdf

[xviii] Cartype, “Body by Fisher,” https://cartype.com/pages/346/body_by_fisher; Detroit Historical Society, “The Fisher Family Story,” https://detroithistorical.org/blog/2021-11-16-fisher-family-story .

[xix] “The Fisher Family Story,” supra.

[xx] Id.

[xxi] “Body by Fisher,” supra.

[xxii] Id.

[xxiii] From “Apple History 2004,” https://igotoffer.com/apple/history-apple-2004

[xxiv] See “The Untold Story: How the iPhone Blew Up the Wireless Industry,” Wired, 2008, https://www.wired.com/2008/01/ff-iphone/?currentPage=1; see also Apple Reports First Quarter Results, January 2007, https://www.apple.com/newsroom/pdfs/q207data_sum.pdf

[xxv] From excerpts in P. Hise, “How the Wright Brothers Blew It,” Forbes, Nov. 19, 2003, https://www.forbes.com/2003/11/19/1119aviation.html?sh=697fa8cf1bda

[xxvi] From Combs, Harry, Kill Devil Hill: Discovery the Secret of the Wright Brothers, (1979), pp. 68-71.

[xxvii] The defunct law firm that is under discussion should not to be confused with the risk, benefits, and business solutions company, Sedgwick (www.sedgwick.com)

[xxviii] J. Goodnow, “Sedgwick: Death by Billable Hours,” Above the Law, Dec. 1, 2017, https://abovethelaw.com/2017/12/sedgwick-death-by-billable-hours/

[xxix] Id.

[xxx] Id.

[xxxi] Fisher realized that automobiles would crush demand for carriages. Apple recognized that with increasing sophistication, competitive smart phones risked creating alternatives to the lucrative Apple music universe.

[xxxii] Hise, supra.

[xxxiii] “Situations emerge in the process of creative destruction which many firms may have to perish that nevertheless would be able to live in vigorously and usefully if they could weather a particular storm.” [xxxiii] J. Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy.

[xxxiv] Viguerie, Calder, and Hindo, sura.

[xxxv] Id.

[xxxvi] L. Abramson, “Why Are So Many Law Firms Trapped in 1995?”, The Atlantic, October 1, 2015, https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/10/why-are-so-many-law-firms-trapped-in-1995/408319/

[xxxvii] Id.